Renewal Theology

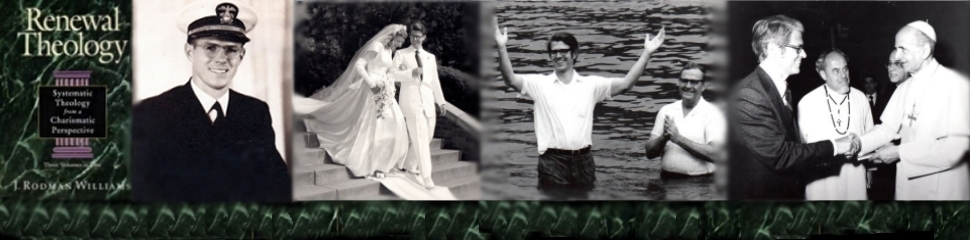

featuring the works of theologian J. Rodman Williams

Renewal Theology

- Home

- About Renewal Theology

- Renewal Theology Reviews

- Renewal Theology Excerpt and Online Bookstores

- Audio Teachings

Media

Published Online Books

A Theological Pilgrimage

- Preface and Personal Testimony

- 1. Renewal in the Spirit

- 2. A New Era in History

- 3.The Upsurge of Pentecostalism

- 4. The Person & Work of the Spirit

- 5. Baptism in the Holy Spirit

- 6. The Missing Dimension

- 7. The Charismatic Movement & Reformed Theology

- 8. God's Mighty Acts

- 9. Why Speak in Tongues?

- 10. The Holy Spirit & Eschatology

- 11. A Pentecostal Theology

- 12.The Greater Gifts

- 13. Biblical Truth & Experience

- 14. Theological Perspectives of the Pentecostal/Charismatic Movement

- 15. The Gifts of the Holy Spirit and Their Application to the Contemporary Church

- 16. The Engagement of the Holy Spirit

- Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Conclusion

The Gift of the Holy Spirit Today

Ten Teachings

- 1. God

- 2. Creation

- 3. Sin

- 4. Jesus Christ

- 5. Salvation

- 6.The Holy Spirit

- 7. Sanctification

- 8. The Church

- 9. The Kingdom

- 10. Life Everlasting

The Pentecostal Reality

- Preface

- 1. The Pentecostal Reality

- 2. The Event of the Spirit

- 3. Pentecostal Spirituality

- 4. The Holy Spirit & Evangelism

- 5. The Holy Trinity

Published Online Writings

Prophecy by the Book

- 1. Introduction: The Return of Christ

- 2. Procedure in Studying Prophecy

- 3.The New Testament Understanding of Old Testament Prophecy

- 4. Israel in Prophecy

- 5. The Fulfillment of Prophecy

- 6. Tribulation

- 7. The Battle of Armageddon

- 8. The Contemporary Scene

Scripture: God's Written Word

- 1. Background

- 2. Evidence of Scripture as God's Written Word

- 3. The Purpose of Scripture

- 4. The Mode of Writing

- 5. The Inspiration of Scripture

- 6. The Character of the Inspired Text

- 7. Understanding Scripture

The Holy Spirit in the Early Church

Other Writings

Chapter 7 - The Charismatic Movement and Reformed Theology

I. A Profile of the Charismatic Movement

The charismatic movement1 began within the historic churches in the 1950s. On the American scene it started to attract broad attention in 1960, with the national publicity given to the ministry of the Reverend Dennis Bennett, an Episcopalian in Van Nuys, California. Since then there has been a continuing growth of the movement within many of the mainline churches: first, such Protestant churches as Episcopal, Lutheran, and Presbyterian; second, the Roman Catholic (beginning in 1967); and third, the Greek Orthodox (beginning about 1971).2 By now the charismatic movement has become worldwide and has participants in many countries.

As one involved in the movement since 1965, I should like to set forth a brief profile of it.3 A profile of the charismatic movement within the historic churches would include at least the following elements: (1) the recovery of a liveliness and freshness in Christian faith; (2) a striking renewal of the community of believers as a fellowship (koinonia) of the Holy Spirit; (3) the manifestation of a wide range of "spiritual gifts," with parallels drawn from 1 Corinthians 12-14; (4) the experience of "baptism in the Holy Spirit," often accompanied by "tongues," as a radical spiritual renewal; (5) the reemergence of a spiritual unity that essentially transcends denominational barriers; (6) the rediscovery of a dynamic for bearing comprehensive witness to the Good News of Jesus Christ; and (7) the revitalization of the eschatological perspective.

Persons in the charismatic movement ordinarily stress this first. This may be expressed in a number of ways.

For example, the reality of God has broken in with fresh meaning and power. God, who may have seemed little more than a token figure before, has now become vividly real and personal to them. Jesus Christ, largely a figure of the past before, has now become the living Lord. The Holy Spirit, who previously had meant almost nothing to them, has become an immanent, pervasive presence.

The Bible, which may have been thought of before as mostly an external norm of Christian faith or largely as a historical witness to God's mighty deeds, has become also a testimony to God's contemporary activity. It is as if a door had been opened, and walking through the door they found spread out before them the extraordinary biblical world, with dimensions of angelic heights and demonic depths, of Holy Spirit and unclean spirits, of miracles and wonders- -a world in which now they sense their own participation. The supposed merely historical (perhaps legendary for some) has suddenly taken on striking reality.

Prayer, formerly little more than a matter of ritual and often practiced hardly at all, becomes a joyful activity often carried on for many hours. The head of a theological seminary now involved in the charismatic movement speaks of how his administrative routine has been revolutionized: the first two hours in the office, formerly devoted to business matters, have been replaced by prayer; only thereafter comes the business of the day.

The Eucharist has taken on fresh meaning under the deepened sense of the Lord's presence- -the doctrine of Real Presence has become experiential fact. The Table has become an occasion of joy and thanksgiving far richer than they had known before.

All of Christian faith has been enhanced by the sense of

inward conviction. Formerly there was a kind of hoping against

hope; this has been transformed into a buoyant "full assurance

of hope" (Heb. 6:11).

There has occurred in the charismatic movement a striking emergence of the gathered community as a koinonia of the Holy Spirit. People in this movement are seldom loners; they come together frequently for fellowship in the Spirit. Formerly for many the gathered church had become a matter of dull routine, but now they are eager to be together in fellowship as often and as long as possible.

The fellowship of faith has become greatly deepened and heightened

as a fellowship in the Spirit. Here there is first of all a new

note of praise to God. The mood of praise- -through many

a song and prayer and testimony- -is paramount in the charismatic

fellowship. Indeed, the expression "Praise the Lord"

has become the hallmark of the movement. An Episcopal bishop,

commenting on what had happened to him recently, said, "After

centuries of whispering liturgically, 'Praise ye the Lord,' it

suddenly comes out more naturally- -and it's beautiful." The

"joy of the Lord" is another common expression,

and in charismatic fellowships everywhere there are frequent expressions

of enthusiasm, delight, rejoicing in the presence of the Lord.

As one chorus that is sung puts it, "It is joy unspeakable

and full of glory; and the half has never yet been told!"

Often there are evidences of exuberance such as hand clapping

and laughter. Many expressions of love in the Lord are

common, such as the unaffected embracing of one another in the

name of Christ, the quick readiness to minister to others within

the fellowship (often through the laying on of hands with prayer),

and the sharing of earthly goods and possessions through varying

expressions of communal life. Much else could be added, but suffice

it to say that the gathered fellowship has become for many an

exciting, eventful koinonia of the Holy Spirit.

Of striking significance is the manifestation of a wide range of spiritual gifts, or charismata. The gifts of 1 Corinthians 12 have become very meaningful for people in the renewed fellowship of the Spirit. There is the fresh occurrence of all the Corinthian spiritual manifestations: the word of wisdom, the word of knowledge, faith, gifts of healing, working of miracles, prophecy, discernment of spirits, tongues, and the interpretation of tongues (1 Cor. 12:8-10).

A number of things may be said about these gifts. First, they are all understood as extraordinary- -the word of wisdom just as much as gifts of healing, the word of knowledge as working of miracles, faith as discernment of spirits, prophecy as tongues. They are not essentially expressions of natural prowess but are spiritual manifestations; that is, they occur through the activity of the Holy Spirit. Second, these gifts are not viewed as private possessions but operate within the context of the koinonia for the edification of the gathered group. Third, these gifts are earnestly sought after and prayed for, not for the sake of display or novelty, but because it is believed that the Lord wants to express Himself through these various means; hence, all the gifts are essential for the harmonious functioning of the body. Fourth, among the gifts prophecy is especially valued, for in the charismatic fellowship this is heard as a direct dominical utterance (a "thus says the Lord") that has great power to edify the believers and to bring under judgment ("God is in this place!"- -see 1 Cor. 14:25) any unbelievers who might be present. Fifth, these gifts of 1 Corinthians 12-14 are not viewed in isolation from other charismata such as are found in Romans 12:6-8 and 1 Peter 4:10-11, all of which are gladly recognized and desired; however, the Corinthian charismata are understood to represent a kind of profound opening up of the full range of spiritual manifestations.

It is important to add that in the charismatic fellowship the

focus is not on the gifts but on the Giver, Jesus Christ. The

meeting of the fellowship is for the purpose of proclaiming "Jesus

is Lord" by the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 12:3), and whether the

pneumatic manifestations do or do not occur is altogether incidental

to the praise that is continually offered to His name.

The charismatic movement lays strong emphasis on the experience described as "baptism in the Holy Spirit" and its frequent concomitant of "speaking in tongues." Indeed, it may be said that the experience of this "baptism" represents the spiritual breakthrough out of which people move into the varied charismatic expressions and into their fresh and lively faith.

Persons in the charismatic movement come into this experience of "spiritual baptism" out of various backgrounds: non-Christian, nominally Christian, even longtime Christian. The word "baptism" signifies for them an immersion in spiritual reality so that, whatever may have been the situation before, this is a spiritual experience of far greater intensity. Or to put it a bit differently, this is an experience of "fullness"- -"filling with the Spirit"- -that cannot be measured in quantitative terms alone, for there is the sense of entrance upon a fresh dimension of fullness of the Spirit. Wherever they were before spiritually, such persons now experience the exhilaration of a breakthrough of the Holy Spirit into their total existence.

This "baptism with the Spirit" is wholly related in the charismatic movement to faith in Jesus Christ. It is ordinarily thought of not as a "second work of grace" but as a deepening of the faith that is grounded in Christ and the new life in His name. The immediate background may have been that of an increased hunger and thirst after God, a desire to be "filled with the Spirit" for more effective witness, or simply a kind of total yielding to Christ wherein He now becomes in a new way the Lord of all of life. Prayer, often persistent and expectant, is frequently the spiritual context, and the laying on of hands for the "fullness" of the Spirit is often the occasion when this "baptism" occurs. In every case, the experience of spiritual baptism flows out of the life in Christ, and is understood to be the effusion of His Spirit with power for praise, witness, and service.

The occurrence of "speaking with tongues," which so often accompanies this spiritual baptism, is ordinarily experienced as one of transcendent praise. Many persons coming into this dimension of fullness find their ordinary speech transcended by a kind of spiritual utterance in which the Holy Spirit provides a new language of jubilation and praise. Here there is a moving past the highest forms of conceptual expression into the spiritual, wherein there is indeed meaning and content but on the level of transcendent communication. This communication is directed not to man but to God, whose glory and deeds are extraordinarily magnified.

This language of praise not only occurs frequently at the initial

moment of "baptism with the Spirit," but also continues

as a prayer language in the life of faith. To "pray in the

Spirit" (Eph. 6:18, Jude 20) now becomes filled with new

significance as a deep spiritual utterance possible at all times.

Most persons in the charismatic movement will speak of their time

of prayer as praying with both the mind and the spirit (1 Cor.

14:15), wherein there is alternation between conceptual and spiritual

utterance. This may be not only for praise but also as prayer

for others- -as the Spirit makes deep intercession according to

the will of God (Rom. 8:26-27).

One of the most striking features of the charismatic movement is the resurgence of a deep unity of spirit across traditional and denominational barriers. For though the movement is occurring within many historic churches- -and often bringing about unity among formerly discordant groups- -the genius of the movement is its transdenominational or ecumenical quality.

This may be noted, for one thing, from the composition of the charismatic group that meets for prayer and ministry. It is not at all unusual to find people fellowshiping and worshiping together from traditions as diverse as classical Pentecostal, mainline Protestant, and Roman Catholic. What unite them are matters already mentioned: a renewed sense of the liveliness of Christian faith, a common expectancy of the manifestation of spiritual gifts for the edification of the community, and, most of all, a spiritual breakthrough that has brought all into a deepened sense of the presence and power of God. The overarching and undergirding unity brought about by the Holy Spirit has now become much more important than the particular denomination.

Herein is ecumenicity of a profound kind in which there is a rediscovery of the original wellsprings of the life of the church. Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox charismatics alike are going back far behind the theological, liturgical, and cultural barriers that have long separated them into a recovery of the primitive dynamism of the early ecclesia. It is this common rediscovery of the New Testament vitality of the Spirit that unites people of diverse traditions and remolds them into a richer and fuller koinonia of the Holy Spirit.

The charismatic movement has, I believe, been well described as

"the chief hope of the ecumenical tomorrow."4 For this

is "spiritual ecumenism," not organizational or ecclesiastical

ecumenism. With all due appreciation for the ecumenical movement,

which has helped to bring churches together in common concern

and has now and again brought about visible unity, this cannot

be as lasting or far-reaching as the ecumenism emerging from a

profound inward and outward renewal of the Holy Spirit. For this

ecumenism is not an achievement derived from a common theological

statement, an agreed upon polity, or an acceptance of differing

liturgical expressions. It is rather that which is given through

Jesus Christ in the renewed unity of the Holy Spirit.

The charismatic movement represents the rediscovery of a fresh thrust for witness to the gospel. This may be illustrated by a reflection upon the previous points in the context of the continuing command of Christ to the church: "You shall be my witnesses." What primarily has been recovered through "baptism in the Spirit" is the plenitude of power for witness. Many before had found their witness to the Good News weak and ineffectual; now it has become much more dynamic and joyful. It is not so much a matter of strategies and techniques of witness as of transparent and vibrant testimony to the new life in Jesus Christ. What it means to be Christ's witness- -and not simply to "talk" it- -is a new experience for many in the charismatic renewal. That "the kingdom of God does not consist in talk but in power" (1 Cor. 4:20) is a fresh and exciting discovery!

Among the common tensions within the church are the competing claims of personal and social witness: the gospel as a call to personal conversion and a call to minister to a wide range of human needs. Frequently it is said that the question is one not of either/or but of both/and, for the good news concerns the whole of man in his personal and corporate existence. Therefore the question is often put as one of relating the two dimensions, and giving proper attention to each. But, however true the importance of a comprehensive witness, the need actually runs much deeper, namely, that of a fresh dynamic or power for pursuing and accomplishing both personal and social aims. Indeed, today one finds a "tired" personal evangelism as much as a "tired" social concern- -each, perhaps unknowingly, desperate for a new anointing of power and vision.

In the charismatic movement there are clear evidences that the contemporary endowment of the Spirit is making for more effective witness, both personal and social. It is apparent on many charismatic fronts that there are both a fresh kind of "reality evangelism"- -a joyous, often indirect but highly potent, form of witness about the new life in Christ- -and many vigorous and creative expressions of concern for the manifold disorders in personal and corporate life.5

The charismatic movement signalizes a revitalization of the eschatological orientation of the Christian faith. For many persons now active in the movement the whole area of eschatology had meant very little. Whatever the Christian faith had to say, there was a consciousness that it dealt with the present: some kind of amelioration or renovation of the prevailing human situation. Scarcely more than passing thought was given to "last things." Others in the movement had viewed Christian faith as focusing almost exclusively on the future: the resurrection, parousia, kingdom, and so on. Salvation itself was largely a matter to be experienced at the "end." The present world was scarcely a place of God's joyful presence- -but one could hope for something better in the future.

What is patently happening among people in the charismatic movement is the recovery of a lively sense of present and future under the impact of the Holy Spirit. For those preoccupied with the future, the present has now taken on rich significance through the activity of the Holy Spirit. All of life is now pulsating with the vitality and dynamism of the divine presence and action. For those who previously could see little beyond the contemporary world, the future has taken on an exciting meaning because of the new sense of Christ. He is so personally real now that there is a fresh yearning for His future coming in glory, the establishment of the kingdom, and the fulfillment of all things. Because of what has so abundantly happened in the now, the future prospect is viewed with keen anticipation. The result is a vital eschatology in which present and future are united through the dynamism of the Holy Spirit.

In reflecting upon the charismatic movement from a Reformed viewpoint I shall, because of space limitations, narrow this basically to a consideration of John Calvin's perspective on the Holy Spirit, and briefly note some of the development since that time. I shall also limit myself to a consideration of only the first five of the seven distinctives (in the profile above), making extended comments in the two areas that are most commonly discussed, namely, the charismata and "baptism in the Holy Spirit."

In the first matter of the recovery of liveliness and freshness in Christian faith Reformed theology can surely rejoice. Going back to the Reformed father, John Calvin, and particularly to his Institutes of the Christian Religion, one finds continuing testimony of the need for vital experience. The knowledge of God, Calvin affirms, "consists more in living experience than in vain and high-flown speculation;"6 there is need for being "truly and heartily converted" to Christ;7 and every Christian is called to "glory in the presence of the Holy Spirit."8 Calvin called his Institutes, for all its theological content, not a "summa theologiae" but a "summa pietatis,"9 and would summon all his readers to that lively faith without which it is hardly worth being called a Christian. The charismatic movement (scarcely foreseen by Calvin) with its emphasis on vital and "living experience" would surely seem to be in accord with the spirit of Calvin and the best of the Reformed tradition.10

In the second area of the church as "koinonia of the Holy Spirit" there would seem to be less emphasis in Calvin and the Reformed tradition. Calvin recognized the importance of common worship and praise, but his view of the church as existing "wherever we see the Word of God purely preached and heard, and the sacraments administered according to Christ's institution"11 too easily leads to an overemphasis on instruction and order. As important as the marks of preaching and sacraments are, it is only, in addition, people living in the koinonia of the Spirit who represent the fully functioning ecclesia. Thus the charismatic movement signalizes, I believe, an enrichment of the Reformed tradition in stressing a possible "third mark" of the church, namely, that it exists wherever people gather for praise, fellowship, and ministry in the koinonia of the Holy Spirit.12

Now we turn to a more extended consideration of the third area, namely, that having to do with the full range of the charismata. We shall note both Calvin's somewhat mixed position, and the increasing Reformed recognition of all the biblical gifts as having continuing validity.

In looking at Calvin's view of the gifts of the Spirit we observe several things. It is apparent, first, that Calvin speaks quite affirmatively of the gifts and graces of the Holy Spirit. For example, he writes, "We are furnished, as far as God knows to be expedient for us, with gifts of the Spirit, which we lack by nature."13 Again, "He (the ascended Christ)...sits on high, transfusing us with his power that he may quicken us to spiritual life, sanctify us by his Spirit, adorn his church with diverse gifts of his grace."14 Not only does Calvin speak positively of the gifts in general but also of the seemingly more extraordinary, which he terms variously as "miraculous powers," "manifest powers and visible graces (or gifts)," and "singular gifts." For example, Calvin writes about the laying on of hands by the apostles that it was not only for the reception of a person into the ministry, but "they used it also with those upon whom they conferred the visible graces of the Spirit [Acts 19:6]."15 He refers to the gift of tongues as "the singular gift of tongues,"16 speaks of the gift of tongues along with prophecy as special gifts of God,17 and declares that "the Holy Spirit has here18 honoured the use of tongues with neverdying praise." The New Testament gift of tongues, according to Calvin, had double significance: both for preaching and adornment. Regarding the Gentiles at Caesarea, Calvin writes: "So...they did glorify God with many tongues. Also...the tongues were given them not only for necessity, seeing the Gospel was to be preached to strangers and to men of another language, but also to be an ornament and worship [or 'honour'] to the Gospel."19 Thus, in general, Calvin speaks affirmatively of the biblical charismata.

Second, Calvin tends to view the "extraordinary" gifts as having irrevocably ceased. One reason given for this is that God provided these gifts only to illuminate the new proclamation of the gospel:

The Lord willed that those visible and wonderful graces...which he then poured out upon his people, be administered and distributed by his apostles through the laying on of hands.... But those miraculous powers and manifest workings...have ceased; and they have rightly lasted only for a time. For it was fitting that the new preaching of the Gospel and the new Kingdom of Christ should be illumined and magnified by unheard-of and extraordinary miracles.20

Another reason given for the cessation of the unusual gifts is that people so quickly corrupted them that God simply took them away. Calvin writes that "the gift of tongues, and other such like things, are ceased long ago in the Church....many did translate that [the gift of tongues] unto pomp and vain glory....No marvel if God took away that shortly after which he had given, and did not suffer the same to be corrupted with longer abuse."21 So whether because of no further need (the "new preaching" being a thing of the past) or because of the corruption that so rapidly set in, the extraordinary gifts, by God's decision, have ceased once and for all.

It may be important to observe that Calvin does not relate the cessation of the extraordinary gifts to the passing off the scene of the apostles. It is not that the apostles have ceased but that the [supra] "miraculous powers and manifest workings have ceased." Since the ministry of the miraculous gifts has been withdrawn, there is no longer need, for example, of the laying on of hands. "If this ministry [of the gifts] which the apostles then carried out still remained in the Church, the laying on of hands would also have to be kept. But since that grace [or gift] has ceased to be given, what purpose does the laying on of hands serve?"22

Third, Calvin at times suggests that if we but had more faith and less slothfulness, the "gifts and graces" of the Holy Spirit would be poured out afresh. For example, in reference to the "rivers of living water" (John 7:38) that Jesus said would come from those who had received the Holy Spirit, Calvin declares that the rivers signify "the perpetuity, as well as the abundance of gifts and graces of the Holy Spirit...promised to us." However, Calvin thereafter adds, "How small is the capacity of our faith, since the graces of the Holy Spirit scarcely come into us by drops...[they] would flow like rivers, if we gave due admission to Christ; that is, if faith made us capable of receiving Him."23 Though Calvin does not here speak as such of "miraculous gifts" and "visible graces," it is significant that he relates the paucity of gifts and graces not to a divine termination of them but to our little faith. In similar vein Calvin writes:

That we lie on the earth poor, and famished, and almost destitute of spiritual blessings, while Christ now sits in glory at the right hand of the Father, and clothed with the highest majesty of government, ought to be imputed to our slothfulness, and to the small measure of our faith.24

Thus, though Calvin does not himself directly draw the conclusion, it may be possible to say that the dearth of spiritual blessings, of gifts and graces, whether ordinary or extraordinary, is not due to divine fiat (namely, no more miraculous workings forever) but to lack of human faith and zeal. What if we gave "due admission to Christ," what if the gifts and graces thereby began to "flow like rivers?" Would there be any limit set on even the most unusual of the charismata of the Holy Spirit?25

It is my conviction that while Calvin, the father of Reformed theology, may be cited as depicting the permanent cessation of the extraordinary charismata, his attitude is essentially positive. His obvious esteem for the "wonderful graces" of the Holy Spirit, for the "singular gift of tongues," etc., and his concern about our spiritual slothfulness and little faith whereby we receive so little of God's gifts and graces, could readily combine to point to a more comprehensive charismatic position. In other words, the renewed manifestation of the full range of charismata in our day, while not according to Calvin's technical position,26 corresponds with his high evaluation of all the gifts and with his view that God is eager to pour out his spiritual blessings upon those who have faith and zeal. It might also have been the case that if Calvin had personally experienced the extraordinary gifts of the Spirit, his theology- -already straining in an affirmative direction- -would have been revised to make room for them. Since Calvin never gives any exegetical basis for the cessation of the extraordinary gifts (not even that of apostolic office), it seems apparent that he writes out of lack of experience.27 With experience confirming the biblical record Calvin, I believe, would readily have taken a fully charismatic position.

The situation today in Reformed theology generally could be called that of openness to the full range of charismatic gifts. Despite the "Warfield position" of some wherein the extraordinary gifts of the Spirit are linked to the original apostolic office,28 there is a growing readiness to recognize the contemporary validity of the charismata. Karl Barth, for example, in writing about extraordinary manifestations of the Spirit (in the context of 1 Corinthians 13) says, "Where these are lacking, there is reason to ask whether in pride or sloth the community as such has perhaps evaded this endowment, thus falsifying its relationship to its Lord, making it a dead because a nominal and not a real relationship."29 Emil Brunner writes: "The miracle of Pentecost, and all that is included under the charismata- -the gifts of the Spirit- -must not be soft-pedaled from motives of a theological Puritanism."30 Even the conservative Reformed theologian A. A. Hoekema, who is opposed to present-day glossolalia ("a human reaction...psychologically induced"), nonetheless concedes that "we certainly cannot bind the Holy Spirit by suggesting that it would be impossible for him to bestow the gift of tongues today."31

A number of recent Reformed documents on the charismatic movement have likewise recognized the validity of the gifts for the present day. On the matter of glossolalia the Dutch Reformed Church of the Netherlands, in its Pastoral Letter of 1960 (probably the first ecclesiastical statement dealing with the charismata) about The Church and the Pentecostal Groups, says: "We think it presumptuous to maintain that tongue-speaking was something only for the beginning of Christianity. Biblical evidence in Acts and 1 Cor. 12 and 14 are much too explicit for that....The fact that tongue-speaking also has a meaning for our time is therefore not to be ruled out."32 The former United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. in its 1970 document on The Work of the Holy Spirit declares that "we cannot...follow the view of some theologians that the purely supernatural gifts ceased with the death of the apostles. There seems no exegetical warrant for this assumption."33 Again: "We believe that the Holy Spirit is witnessing to the church that it should be 'praying and sighing' for his ministry and manifestations, but too often the charismatic dimension is being reduced to the level of psychological dynamics and dismissed as an emotional aberration."34 In the 1974 Report of the Panel on Doctrine of the Church of Scotland, entitled The Charismatic Movement Within the Church of Scotland, there is an unmistakable difference with Calvin on the cessation of certain spiritual gifts. Criticizing Calvin's interpretation of Mark 16:17,35 the Panel says:

Since God has finally spoken in Christ, what have undoubtedly ceased are new revelations. What has not ceased according to Scripture is the promise of gifts. The promise in Mark was made "to them that believe," and this is a promise valid for all times, and to the end of time. There is no warrant in Scripture for confining it to the "commencement" of the Gospel.36

In a "Brief Summary of Conclusions" the Panel states: "The gifts of the Spirit are to be expected. Where there is expectation, the Church may well be endowed with a larger and more evident measure of these gifts than a church which has long believed that these gifts have ceased may hope for."3

We turn next to the consideration of "baptism in the Holy Spirit" in Reformed theology. It will be recalled that this represents in the charismatic movement a spiritual breakthrough in which varied charismatic expressions become operative, and in which the Christian life is variously renewed. Here Reformed theology is much more ambivalent, and as yet no consensus has emerged.

Some of the ambivalence is found in Calvin himself. Calvin in dealing with the expression "baptized in the Holy Spirit" has a double understanding which he never resolves. On the one hand he views "baptism in the Spirit" as the means of salvation or regeneration:

We have said that perfect salvation is found in the person of Christ. Accordingly, that we may become partakers of it "he baptizes us in the Holy Spirit and fire"...bringing us into the light of faith in his gospel and so regenerating us that we become new creatures...and he consecrates us, purged of worldly uncleanness, as temples holy to God.38

Similarly Calvin writes that "to baptize by the Holy Spirit and by fire is to confer the Holy Spirit, who in regeneration has the function and nature of fire."39 Calvin does not hesitate to say elsewhere that water baptism is little more than an outward sign, but that Christ is "the author of inward grace,"40 that is, the grace of salvation.

On the other hand, Calvin also speaks of "baptism in the Holy Spirit" as having to do with the conferring of the gifts of the Holy Spirit:

[It is] the visible graces of the Holy Spirit given through the laying on of hands. It is nothing new to signify these graces by the word "baptism." As on the day of Pentecost, the apostles are said to have recalled the words of the Lord about the baptism of fire and of the Spirit. And Peter mentions the same thing...when he had seen those graces poured out upon Cornelius, his household, and kindred (Acts 11:16).41

Again in his Commentary on Acts, Calvin says:

It is no new thing for the name of baptism to be translated unto the gifts of the Spirit, as we saw in the first and in the eleventh chapters (Acts 1:5, and 11:6) where Luke said, that when Christ promised to his apostles to send the Spirit visible, he called it baptism....When the Spirit came down upon Cornelius, Peter remembered the words of the Lord, "Ye shall be baptized with the Holy Ghost."42

Calvin's position is a peculiar one. Exegetically it seems that he favors the latter position, namely, baptism in the Spirit as not identical with regeneration but with the "visible" gifts of the Spirit. Yet since he views those gifts as having been withdrawn (as we have earlier noted), baptism in the Spirit from this perspective can actually have no relevance for the church today. Hence, Calvin's first position (Spirit baptism = regeneration)-even though less satisfactory- -is seemingly the only one that relates to a continuing possibility. Of course, if Calvin had been able freely to embrace the charismata, then baptism with the Spirit could have been understood as the ongoing possibility of charismatic endowment.

It is quite significant that Calvin views the Christian life since apostolic times as not missing anything essential through the disappearance of this early charismatic endowment. In other words it is possible, from this perspective, to be Christian (regenerated, new creatures, etc.) and not baptized in the Spirit.

Now let us raise the further question: assuming Calvin is right in his exegetical identification of baptism in the Spirit with charismatic endowment, what if the deeper issue were not basically the gifts (charismata) but the gift of the Spirit? What if the real lack since the early church often has been not extraordinary gifts but that endowment of the Spirit wherein the charismata become operative? What if baptism in the Spirit refers, as Calvin in places exegetically maintains, to something not essential to Christian existence, but to a gracious gift wherein there is a deepened sense of the Spirit's presence and power along with various charismatic manifestations? We could then say that Calvin helped prepare the way by his recognition of baptism in the Spirit as reaching beyond salvation history into the realm of spiritual endowment- -even if he identified such a baptism with the charismata and largely saw no hope of their recurrence.

In brief, Calvin's signal contribution to contemporary understanding is his recognition that there has been something in the dimension of the Spirit often missing since apostolic times. It is not the actuality of salvation or regeneration that is the issue here but the matter of charismatic endowment: in the broadest sense, the endowment of the Holy Spirit with His gifts. This of course is what the charismatic movement of our time is also saying, namely, that this aspect of the Spirit's activity is again becoming operational. In that sense "baptism in the Holy Spirit"- -a newly recovered dimension- -is grounded in Calvin's own pneumatological orientation.

Within recent years in Reformed theology there have been signs of recognition of "baptism in the Spirit" as a long neglected dimension of the Holy Spirit's activity. So far as I know, Professor Hendrikus Berkhof of Leiden was the first to point this direction in his book, The Doctrine of the Holy Spirit. He speaks therein of how, in addition to justification and sanctification, various "Revivalists and Pentecostal movements...experienced still another blessing of the Holy Spirit in the life of the individual which is now widely known as the 'filling by the Holy Spirit' or 'the baptism by the Holy Spirit.'"43 Then after discussing the work by the Holy Spirit in Acts, Berkhof emphasizes:

The main line is clear: by a special working of the Spirit, the faithful are empowered to speak in tongues, to prophesy, to praise God, that is, to give a powerful expression of God's mighty acts to those around them.44

We may note that Berkhof's special point is not so much the charismata themselves as the empowering for their expression. Then after a discussion of Paul's treatment of the spiritual gifts in 1 Corinthians 12-14, Berkhof adds:

For him also [as with Luke] the work of the Holy Spirit is not exhausted in justification and sanctification; an additional working is promised and must therefore be sought. All this leads us to the conclusion that the Pentecostals are basically right when they speak of a working of the Holy Spirit beyond that which is acknowledged in the major denominations.45

By this statement Berkhof has sprung open the charismatic dimension in Reformed theology, and become in many ways the theological precursor of the contemporary charismatic movement in the Reformed tradition.

On the ecclesiastical front a most significant development has been the recognition of this "additional working" of the Spirit by the former Presbyterian Church, U.S. (Southern), in its statement entitled "The Person and Work of the Holy Spirit: With Special Reference to 'the Baptism of the Holy Spirit.'"46 A part of the statement reads:

Baptism with the Holy Spirit, as the Book of Acts portrays it, is a phrase which refers most often to the empowering of those who believe to share in the mission of Jesus Christ....believers are enabled to give expression to the gospel through extraordinary praise, powerful witness, and boldness of action. Accordingly, those who speak of such a "baptism with the Spirit," and who give evidence of this special empowering work of the Spirit, can claim Scriptural support. Further, since "baptism with the Spirit" may not be at the same time as baptism with water and/or conversion, we need to be open-minded toward those today who claim an intervening period of time. If this experience signifies in some sense a deepening of faith and awareness of God's presence and power, we may be thankful.47

Finally (the last paragraph begins): "It is clear that there is Biblical and Reformed witness concerning baptism of the Holy Spirit and special endowments of the Holy Spirit in the believing community."48

Now I do not want to suggest that there is unanimity in Reformed circles regarding this "additional working" of the Holy Spirit. Neither the former United Presbyterian Church nor the Church of Scotland report adopts the above position. The United Presbyterian report, while recognizing that "the predominant testimony of the Book of Acts concerning the Holy Spirit concentrates on the outpouring, the gift, the reception, the falling of the Holy Spirit upon Christian believers," argues semantically that "nowhere is reference made to 'the baptism in (or, with) the Spirit.'"49 Actually in this report there is a cautious drawing away from Acts, the report arguing both that we should give primary attention to the didactic (i.e., non-Acts) portions of the New Testament, and that there is the "notorious difficulty of ascertaining any single, consistent pattern in Acts of the sequence of conversion, reception of the Holy Spirit, and waterbaptism."50 In spite of all this, the Report earlier says: "We must, however, keep in mind that the pattern of empowering by the Spirit revealed in these narratives is both a stimulus for the church today and a help in the understanding of Neo-Pentecostal experience among us"!51 Hence, one senses in the United Presbyterian report both an uncertainty in this area and a desire to be open to what charismatics are experiencing and saying. The Church of Scotland report declares quite bluntly: "From the Reformed point of view, to insist on baptism in the Holy Spirit as an experience subsequent to conversion is to deny the allsufficiency of Christ. Although there are passages in Acts which suggest a theology of subsequence when interpreted literally, there are others which are not in harmony with this."52 The Church of Scotland is obviously also uncomfortable with the narrative in Acts. Still, in the summary, it is significant to note the statement that "the Panel does not deny the reality of an experience which can transform the faith of a believer or give new life to a jaded ministry."53

What, of course, the charismatic movement is saying is that this

transforming experience in the faith of a believer is precisely

what the Book of Acts (for all its alleged inadequacies) is talking

about in terms of "baptism" (outpouring, falling, etc.)

of the Holy Spirit. Here I believe the former Presbyterian Church,

U.S., report is showing the way- -although there is surely room

and need for much further development.

A number of things may now be summarized: First, "baptism in the Holy Spirit," however worded, is not the Holy Spirit active in salvation but in implementation: it is the mighty coming of the Spirit upon those who believe. This coming is not for the origination of faith but belongs to that action of God through Christ in which there is enablement of praise, witness, and service. Second, as the record in Acts demonstrates, this is the action of the "missionary Spirit," who in coming propels the faithful out into the world as a vital part of the mission of Jesus Christ- -"the justified and sanctified are now turned, so to speak, inside out."54 Third, "baptism in the Spirit" presupposes faith in Christ, forgiveness of sins in His name, and therefore is totally grounded in a living relationship to Him as Savior and Lord. Fourth, such a spiritual baptism may be preceded by years in which the Holy Spirit has been active in personal and/or communal life. Now there is a further breakthrough of spiritual endowment and intensity. Fifth, "baptism in the Spirit" points to an immersion in the reality of the Spirit of God. Whatever may have been the relation of the Holy Spirit to the person and/or community before, this spiritual baptism is a flooding of divine presence and power. Sixth, utterance in "tongues" is peculiarly a sign of this spiritual baptism, wherein the depths of the human spirit are probed by the divine Spirit and the consequent language moves past the mental and conceptual into spiritual utterance. In such expression-which is not ecstatic babbling but transcendent praise- -there is declaration of the mighty acts of God and the extolling of His glorious name. Seventh, prayer, self-surrender, expectancy- -openness to "the promise of the Spirit"- -is often the context in which the Holy Spirit is poured out. Even as the heavenly Father delights to "give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him" (Luke 11:13), so may those who ask in faith expect to receive bountifully from His grace.

A word here may be added not about Reformed theology but about the concern frequently expressed in the Reformed and Presbyterian churches for an outpouring of God's Holy Spirit. As far back as 1892 at the World Presbyterian Alliance meeting in Toronto it was said that "there should be a more realizing sense of the necessity of an outpouring of the Spirit." And at the Alliance meeting in 1899 in Washington, D.C., the Council noted that there is "a deepening thirst for a present day experience of the fullness of His [the Spirit's] power."55 All of this of course preceded the birth of the Pentecostal movement in the first decade of the twentieth century. Those who were privileged to be at the 1964 Alliance meeting in Frankfurt, Germany, will recall the theme of the meeting, "Come, Creator Spirit!" in which there was frequent expression of desire for the Spirit to come in fresh power. Dr. W. A. Visser 't Hooft's opening sermon included these remarks:

Veni Creator Spiritus cannot possibly be taken to signify: "Let's have a little bit of Holy Spirit; just enough to put some energy into our sleeping institutions." It can only mean: "Come, Thou living God, Thou Living Christ, Thou Creator Spirit, and transform us altogether, so that we may be truly converted, radically changed."56

It is some such transformation by the Spirit of the living God that is at the heart of the charismatic movement in our time, and bids fair to bring about the radical renewal of the church of Jesus Christ throughout the world.

Finally, we shall make brief reference to the fifth aspect of the charismatic movement- -the striking sense of spiritual unity and communion that transcends traditional denominational barriers. This corresponds well with the genius of the Reformed tradition which since the day of Calvin has had a strong ecumenical orientation. One recalls, for example, Calvin's letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury wherein Calvin bespeaks his own zeal for unity:

This other thing also is to be ranked among the chief evils of our time, viz., that the Churches are so divided, that human fellowship is scarcely now in any repute amongst us, far less that Christian intercourse which all make a profession of, but few sincerely practice.57

This attitude of Calvin, despite occasional departures, belongs to the consciousness of the Presbyterian and Reformed churches. These churches a century ago were the first to form a world confederation (the World Alliance beginning in 1875), and have been active from the inception of the ecumenical movement in the twentieth century.

Hence the charismatic movement, representing a profound unity among Christians of every communion through the renewal of the Holy Spirit, is not only in accord with the spirit of the Reformed tradition but also has a signal contribution to make. Since in the charismatic movement there is a rediscovery of the wellsprings of the life of the church which unite in depth Christians of all denominations- -Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox alike- -then there is realized a major step on the way to the unity of all churches. There may remain, to be sure, many doctrinal, liturgical, and cultural differences, but these can be dealt with from a new perspective under the transcending impact of the Holy Spirit.

Footnotes

1Many prefer the expression "charismatic renewal" to emphasize: (1) that this is not a movement in the sense of an organized effort to achieve certain ends, (2) that since (as will be noted in more detail below) one important aspect of the movement is the renewal of a wide range of biblical charismata, the better, and more precise, name is "charismatic renewal." I shall retain the term "movement," despite the difficulties with the word, because there is actually more involved than charismatic renewal. Indeed what is basic, I believe, is a movement of the Holy Spirit wherein the charismata are reappearing in wide measure. Hence "charismatic movement" is difficult from another perspective. I shall later speak of this also as a dynamic movement of the Holy Spirit wherein the charismata are recurring.

2The first national Orthodox Charismatic Conference was held the summer of 1973 at Ann Arbor, Michigan. National (or International) Episcopal, Lutheran, Presbyterian and Roman Catholic Conferences are now held each year. There are also Baptist, Methodist, Mennonite, and other conferences held regionally and locally throughout the United States.

3My more extended reflection is set out in The Era of the Spirit and The Pentecostal Reality.

4Words of John A. Mackay, former president of Princeton Theological Seminary: "What is known as the charismatic movement-a movement marked by spiritual enthusiasm and special gifts, and which crosses all boundaries of culture, race, age, and church tradition-is profoundly significant....Because 'no heart is pure that is not passionate and no virtue is safe that is not enthusiastic,' the charismatic movement of today is the chief hope of the ecumenical tomorrow" ("Oneness in the Body: Focus for the Future," World Vision, April 1970). (See also chap. 3, "The Upsurge of Pentecostalism," for a fuller quotation.)

5See the book by Larry Christenson (a leading charismatic Lutheran pastor), A Charismatic Approach to Social Action. See also, inter alia, Gathered for Power by charismatic Episcopal priest, Graham Pulkingham. This is a remarkable story of a charismatic parish moving freely in both personal and corporate witness.

6Institutes, 1.10.2 (Battles trans. here and hereafter).

7Ibid., 3.3.25.

8Ibid., 3.2.39. "It is a token of the most miserable blindness to charge with arrogance Christians who dare to glory in the presence of the Holy Spirit, without which glorying Christianity itself does not stand!" It is not without interest that Calvin says this in a section in which he also talks about the gifts of the Holy Spirit. If we say "'we know the gifts bestowed on us by God' [1 Cor. 2:12], how can they yelp against us without abusively assaulting the Holy Spirit?"

9Ibid. Introduction, 51.

10Unfortunately the Reformed tradition has not always held to the attitude of Calvin. Theology hardening into an orthodoxy that left out piety, along with an exaggerated fear of "subjective experience," has often been the picture.

11Ibid., 4.1.9. Emil Brunner astutely observes that "no one will suppose that one of the apostles would recognize again in this formula the Ecclesia of which he had living experience" (The Misunderstanding of the Church, 103).

12In Reformed orthodoxy, after Calvin, the third mark of the church came to be discipline (see, e.g., Leiden Synopsis [40:45]). This is hardly progress in the direction of koinonia of the Spirit!

13Institutes, 2.15.4.

14Ibid., 2.16.16. Also we may recall the words of Calvin in 3.2.39. See note 8 supra.

15Ibid. 4.3.16.

16Ibid., 3.20.33.

17This is done in conjunction with a reference to the power to work miracles wherein, says Calvin, Paul "uses the terms 'powers' and 'faith' for the same thing, that is, for the ability to work miracles. This power or faith, therefore, is a special gift of God, which any impious man can brag about and abuse, as the gift of tongues, as prophecy, as the other graces" (Institutes, 3.2.9).

18Commenting on 1 Corinthians 14:5 (Beveridge trans., here and hereafter regarding Calvin's Commentaries), Calvin's full statement reads: "As it is certain, that the Holy Spirit has here honoured the use of tongues with never-dying praise, we may very readily gather, what is the kind of spirit that actuates those reformers, who level as many reproaches as they can against the pursuit of them." The context incidentally shows that Calvin here understands tongues as foreign languages.

19Commentary on Acts 10:46.

20Ibid., 4.19.6.

21Commentary on Acts 10:44, 46. Also note may be made of Calvin's word regarding Mark 16:17-18-"And these signs will accompany those who believe: in my name they will cast out demons; they will speak in new tongues...they will lay their hands on the sick, and they will recover"-wherein he says, "Though Christ does not expressly state whether he intends this gift to be temporary....yet it is more probable that miracles were promised only for a time, in order to give lustre to the gospel...[also] the world may have been deprived of this honour through the guilt of its own ingratitude" (Commentary on a Harmony of the Evangelists, Mark 16:17. Here both reasons for the cessation of the gifts are suggested.

22Institutes, 4.19.6.

23These quotations are from the Commentary on John 7:38.

24Ibid., John 7:39.

25One other passage from Calvin's Commentary on 1 Corinthians 14:32 may be quoted. Calvin speaks of "how very illustrious that Church was, in respect of an extraordinary abundance and variety of spiritual gifts." Then he adds, "We now see our leanness, nay, our poverty; but in this we have a just punishment, sent to requite our ingratitude. For neither are the riches of God exhausted, nor is his benignity lessened; but we are neither deserving of his bounty, nor capable of receiving his liberality."

26There is not space here to note in detail that a large part of Calvin's position that the extraordinary gifts were withdrawn stems from his opposition to the Catholic teaching about confirmation. Since the Roman Catholics used the laying on of hands for confirmation-"increase of grace"-and supported this practice from some of the texts (e.g., Acts 8:17 and 19:16) that Calvin saw to be referring to the "extraordinary" gifts, he could dismiss confirmation as meaningless since God had withdrawn the gifts. "Since that grace [wherein the gifts were administered] has ceased to be given, what purpose does the laying on of hands serve?" (Institutes, 4.19.6).

27This lack of experience is admitted in a backhanded way where Calvin says that even "the Papists...themselves are enforced to grant that the Church was beautified for a time only with these gifts" (Commentary on Acts 8:16).

28B. B. Warfield wrote concerning the extraordinary gifts: "They were part of the credentials of the Apostles as the authoritative agents of God in founding the church. Their function thus confined them to distinctively the Apostolic Church, and they necessarily passed away with it" (Counterfeit Miracles, p. 6). It may be noted that Warfield's view of the reason for the disappearance of the charismata, namely apostolic demise, is not that of Calvin.

29Church Dogmatics IV/2:828.

30Dogmatics, 3:16.

31What About Tongue-Speaking?, 127-28.

32De Kerk en de Pinkstergroepen, (Herderlijk Schriiven van der Netherlandse Hervormde Kerk, 1960), 41-42.

33See Presence, Power, Praise: Documents on the Charismatic Renewal (Kilian McDonnell, ed., 1:230).

34Ibid., 1:232.

35See note 21 above.

36Presence, Power, Praise, 1:530.

37Ibid., 1:545. This is one of eight brief summary statements.

38Institutes, 3.1.4. In Calvin's Commentary on Matthew 3:11-"He shall baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire"-he similarly says this means that Christ "bestows the Spirit of regeneration."

39Institutes 4.16.25.

40Ibid., 4.15.8.

41Ibid., 4.15.18.

42Commentary on Acts 19:5.

43The Doctrine of the Holy Spirit, 85.

44Ibid., 86.

45Ibid., 87. For a fuller presentation of Berkhof's view see chapter 3, "The Upsurge of Pentecostalism." Also see my preceding chapter, "Theological Perspectives of the Person and Work of the Holy Spirit," the opening two paragraphs.

46Adopted by the General Assembly of 1971. For extended excerpts from this statement, see my chapter 4.

47See Presence, Power, Praise, 1:314.

48Ibid., 1:316.

49Ibid., 1:261. The report quibbles (as I see it) in several places over the contemporary expression "baptism with the Holy Spirit," arguing that the verb "baptize" is always used in the New Testament. This is true; however, the critical question is not one of semantics but whether-however the expression is worded-this refers to something that may happen to Christian believers. The above statement by a semantic dodge avoids the obvious conclusion, namely, "baptism (or 'baptized') with the Holy Spirit" is a parallel expression to "outpouring," "falling," etc., and therefore according to the Book of Acts is something additional possible within Christian experience.

50Ibid.

51Ibid., 1:230.

52Ibid., 1:527. The language of "theology of subsequence" is derived from F. D. Bruner's book, A Theology of the Holy Spirit. It is unfortunate that so much reliance in the report is placed on this basically anti-charismatic treatise, and no reference made, for example, to Berkhof's book. Also though the Presbyterian Church, U.S., report is mentioned in the Introduction to the Church of Scotland report, no reference is made thereafter to it. Incidentally, it is hard to see how the "all-sufficiency of Christ" is denied by an experience subsequent to conversion. If it is the same Christ who turns people to Himself who may then or thereafter baptize them in the Holy Spirit, the sufficiency is totally of Him.

53Ibid., 1:545.

54Berkhof's words in his The Doctrine of the Holy Spirit, 89.

55Marcel Pradervand, "Leaves from the Alliance History," Reformed World, June 1972, p. 78. Dr. Pradervand, General Secretary of the World Alliance from 1948 to 1970, has written me personally, "I for one believe that unless we take the Holy Spirit seriously and are really baptized by the Spirit there is little hope for the traditional Churches."

56As quoted in the Charismatic Communion of Presbyterian Ministers Newsletter, Fall 1974, p. 9.

57Letter to Cranmer, April, 1552, Letters of John Calvin, 132.

Content Copyright ©1996, 2001 by J. Rodman Williams, Ph.D.

| Preface | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9 |

| Chapter 10 | Chapter 11 | Chapter 12 | Chapter 13 | Chapter 14 | Chapter 15 | Chapter 16 | Top |