Renewal Theology

featuring the works of theologian J. Rodman Williams

Renewal Theology

- Home

- About Renewal Theology

- Renewal Theology Reviews

- Renewal Theology Excerpt and Online Bookstores

- Audio Teachings

Media

Published Online Books

A Theological Pilgrimage

- Preface and Personal Testimony

- 1. Renewal in the Spirit

- 2. A New Era in History

- 3.The Upsurge of Pentecostalism

- 4. The Person & Work of the Spirit

- 5. Baptism in the Holy Spirit

- 6. The Missing Dimension

- 7. The Charismatic Movement & Reformed Theology

- 8. God's Mighty Acts

- 9. Why Speak in Tongues?

- 10. The Holy Spirit & Eschatology

- 11. A Pentecostal Theology

- 12.The Greater Gifts

- 13. Biblical Truth & Experience

- 14. Theological Perspectives of the Pentecostal/Charismatic Movement

- 15. The Gifts of the Holy Spirit and Their Application to the Contemporary Church

- 16. The Engagement of the Holy Spirit

- Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Conclusion

The Gift of the Holy Spirit Today

Ten Teachings

- 1. God

- 2. Creation

- 3. Sin

- 4. Jesus Christ

- 5. Salvation

- 6.The Holy Spirit

- 7. Sanctification

- 8. The Church

- 9. The Kingdom

- 10. Life Everlasting

The Pentecostal Reality

- Preface

- 1. The Pentecostal Reality

- 2. The Event of the Spirit

- 3. Pentecostal Spirituality

- 4. The Holy Spirit & Evangelism

- 5. The Holy Trinity

Published Online Writings

Prophecy by the Book

- 1. Introduction: The Return of Christ

- 2. Procedure in Studying Prophecy

- 3.The New Testament Understanding of Old Testament Prophecy

- 4. Israel in Prophecy

- 5. The Fulfillment of Prophecy

- 6. Tribulation

- 7. The Battle of Armageddon

- 8. The Contemporary Scene

Scripture: God's Written Word

- 1. Background

- 2. Evidence of Scripture as God's Written Word

- 3. The Purpose of Scripture

- 4. The Mode of Writing

- 5. The Inspiration of Scripture

- 6. The Character of the Inspired Text

- 7. Understanding Scripture

The Holy Spirit in the Early Church

Other Writings

The Gift of the Holy Spirit Today

Chapter Six - Means

We turn now to a consideration of the gift of the Holy Spirit in relation to water baptism and the laying on of hands. Our concern at this point is the connection between these outward rites and the bestowal of the Spirit. How essential—or dispensable—are they? Is one or the other more closely associated with the gift of the Spirit?

It hardly needs to be said that this has been an area of significant difference in the history of the Church. This is evidenced by the fact, first, that both water baptism and the laying on (or imposition) of hands have been viewed as channels for the gift of the Holy Spirit. Some traditions have held the position that water baptism is sufficient: it is the means whereby the Holy Spirit is given. Accordingly, there is no call for laying on of hands in this situation. Others have held that the laying on of hands is the critical matter: without such, water baptism is incomplete, and there is no gift of the Holy Spirit. How are we to adjudicate between such critical differences?

That this is no small matter would seem undeniable. If the gift of the Holy Spirit is what we have been describing—a veritable outpouring of God's presence and power—and if this gift is vitally related to an outward rite, then the identity of that rite, the question of its essentiality, and its proper execution are critical matters. If, on the other hand, there is no vital connection between the gift of the Holy Spirit and an outward rite, this ought also to be clarified so that we be not burdened by unnecessary concerns. That there needs to be serious reflection in this area is apparent; we can scarcely afford to be uncertain or confused in so important a matter.

Once again we turn primarily to the book of Acts as the basic historical narrative depicting the gift of the Holy Spirit, and now consider its relationship to water baptism and the laying on of hands. There will be some reference also to the Gospels and the Epistles; however, as has been the case in other previous considerations, Acts must be primary because it is the only New Testament record depicting the interrelationship between the gift of the Spirit, the occurrence of water baptism and the laying on of hands.

Let us begin with reflection upon the relation of water baptism to the gift of the Holy Spirit. We are concerned of course with water baptism as a Christian rite—and only incidentally with "the baptism of John" (which is transitional in Acts to Christian baptism).1 How does the rite of Christian baptism relate to the gift of the Spirit? By way of reply we shall set forth a number of declaratory statements and seek to demonstrate these in the five basic narratives having to do with the gift of the Holy Spirit.

However, before proceeding further, we find that water baptism, wherever described in Acts, is performed in the name of Christ only. There are four passages that mention His name in relation to baptism: Acts 2:38; 8:16; 10:48; and 19:5—with the slight variation between "the name of Jesus Christ" (2:38 and 10:48) and "the name of the Lord Jesus" (8:16 and 19:5).2 What is important is the fact of water baptism in the name of Christ only3 (not the variation in the name) and how this will relate to a proper understanding of its connection with the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Now we move on to various declaratory statements. First, water baptism4 may precede the gift of the Holy Spirit. We begin by observing that Peter, following his Pentecostal sermon, asserts: "Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit" (Acts 2:38). Water baptism obviously is depicted as preceding the gift of the Spirit. It is not altogether clear, however, whether a logical or chronological priority is envisioned. Peter's words—"and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit"—could mean either that the gift of the Spirit follows logically and therefore immediately upon water baptism, or that it may happen at some future time. Shortly after Peter's sermon, the Scripture reads: "So those who received his word were baptized, and there were added that day about three thousand souls" (2:41). Nothing is directly said about their receiving the Holy Spirit; however, that such followed directly upon water baptism seems evident in light of the ensuing account (Acts 2:42-47).5

Let us turn next to the Samaritan account where again water baptism is definitely shown to precede the gift of the Spirit. In this instance, however, it is clear that there is an intervening period of several days. The Samaritans "were baptized, both men and women" (Acts 8:12). Later, Peter and John "came down and prayed for them that they might receive the Holy Spirit; for it had not yet fallen on any of them, but they had only been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus" (Acts 8:15-16). So prayer was offered and the laying on of hands was administered with the result that the Samaritans received the Holy Spirit. Hence, there is an unmistakable separation in time between water baptism and the reception of the Holy Spirit.

This passage is quite important in demonstrating that the reception of the Holy Spirit is not bound to the moment of water baptism. It is sometimes argued that there was a special reason for this in the case of the Samaritans, namely, that because of the longstanding prejudice between Jews and Samaritans, it was fitting that the gift of the Holy Spirit be delayed after baptism until representatives from Jerusalem (Peter and John) could come down, and by ministering the Holy Spirit to the Samaritans, demonstrate love and unity. The argument, however, is tenuous indeed, for if delay could happen here, why not in other circumstances?6 Or even if it be agreed that the Jewish-Samaritan situation was maximally one of prejudice, thus calling for additional encouragement from Jerusalem, why not a visit by Peter and John simply to express fellowship and love? Why also the Holy Spirit? In any event the evidence of the text is unambiguous, namely, that regardless of what might later happen, the Samaritans did not receive the Holy Spirit when they were baptized; and this leaves open the possibility that such could happen in other instances.7

That there may be such a delay in many instances is found in the Catholic traditional practice of baptism and later confirmation (the latter sometimes called "the sacrament of the gift of the Holy Spirit" or "the Pentecostal sacrament"), and also in the teaching and experience of large numbers in the contemporary move of the Spirit. In the latter case there is abundant testimony to a reception of the Holy Spirit that frequently takes place some time later than baptism in water; and, indeed, rather than this being an exceptional thing, it quite often occurs.8 Thus—in light of much tradition and experience—the Samaritan happening is a continuing reality.

One other account in Acts likewise specifically shows water baptism as preceding the gift of the Holy Spirit, namely, that of Paul and the Ephesians. We have noted that the Ephesians had earlier been baptized "into John's baptism," but they had not received Christian baptism. So it is that after Paul's words the Ephesians "were baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. And when Paul had laid his hands upon them, the Holy Spirit came on them" (Acts 19:5-6). It is to be observed that, unlike the situation in Samaria, there are no several days' delay between the Ephesians' Christian baptism and their receiving the Holy Spirit. Still there is some chronological separation, however brief, between the rite of water baptism and the laying on of hands. Once again—as in the case of Peter's message to the Jerusalem multitude with baptism following, and as in the case of the Samaritans—the administration of baptism precedes the gift of the Holy Spirit.9

Second, water baptism may follow the gift of the Holy Spirit. On first hearing, this may seem a bit surprising in light of the aforementioned incidents, and especially in view of Peter's words at Pentecost which show an order of repentance, baptism in the name of Christ, and the reception of the Holy Spirit. However, it is apparent that the previous instances are by no means definitive, nor are Peter's words a prescription of the way it always happens. This we shall observe by turning to two other accounts.

The first of these is the narrative of Peter's ministry at Caesarea. As we have seen earlier, while Peter was still delivering his message, the Holy Spirit suddenly fell upon the centurion and those gathered together with him (Acts 10:44). Obviously there had been no water baptism of any kind. However, it is not disregarded, for shortly thereafter Peter declares: "Can any one forbid water for baptizing these people who have received the Holy Spirit just as we have?" And acting on his own declaration, Peter "commanded them to be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ" (10:47-48). Thus water baptism in this case unmistakably follows upon receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit

The other incident concerns Anania's ministry to Saul of Tarsus. Ananias lays hands on Saul that he might be filled with the Holy Spirit (Acts 9:17). The next verse reads: "And immediately something like scales fell from his eyes and he regained his sight. Then he rose and was baptized." Hence it is subsequent to Saul's receiving the Holy Spirit that he is baptized in water by Ananias.

What has been described about water baptism following the gift of the Holy Spirit is not at all unusual in our time. Many persons who have come to a living faith in Christ and the reception of the Holy Spirit have thereafter been baptized in water.10 Often this stems from an intense desire to "go all the way with Christ," to participate corporally in His death and resurrection, to be wholly united to Him. Moreover, such baptism is seldom viewed as optional. Christ instituted it,11 Peter commanded it (see above)—it belongs to Christian initiation and discipleship. So when one adds command to desire, if such persons have not before been baptized in water, it is quite likely to follow!12

We may properly raise a question about the 120 who were filled with the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. What about their water baptism? This is not an easy question to answer. Though doubtless many13 (like the later Ephesians) had participated in John's baptism, it is obvious they had not been baptized in Jesus' name before the event of Pentecost. Hence, the 120 would seem to fall into the same category as Saul of Tarsus and the Caesareans who without Christian baptism received the Holy Spirit. However, unlike in the narratives of Saul and the Caesareans, the Scriptures do not specify that after the 120 had been filled with the Spirit they were baptized in Jesus' name. Quite possibly they were so baptized, along with the 3000 later that day (Peter may have commanded it as he did later with the Caesareans), but there is no clear-cut statement to that effect. It may have been, on the other hand, because of their unique position as original disciples, who existentially were participants in Christ's death and resurrection (living through Good Friday and Easter) and recipients of His life-bestowing forgiveness, that they needed no further tangible rite. For in a certain sense, even more intensely than others after them, they had been baptized into Jesus' reality. In any event, whatever may be the right answer to the question of whether or not the original 120 later received water baptism in Jesus' name, they were similar to Saul of Tarsus and the Caesareans in that they received the Holy Spirit prior to any possible Christian water baptism.

Third—and following upon what has just been said—water baptism is neither a precondition nor a channel for the gift of the Holy Spirit.

It is surely clear by now that water baptism is not a precondition. The very fact, for example, that Saul of Tarsus and the Caesareans received the Holy Spirit before they were water baptized rules out the idea of any precondition. Hence Peter's words, "Repent, and be baptized …and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit," cannot be viewed as a rule that water baptism must occur before the reception of the Spirit. His words, while pointing to what may be the usual pattern, do not establish water baptism as a precondition. Furthermore, if Peter's words were the rule, the rule had just been broken in his case! For as one of the 120 he had received the Holy Spirit with no prior water baptism in Jesus' name.

Many people in the spiritual renewal of our day bear testimony to receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit without a prior Christian baptism. Especially is this the case for those who, like the Caesareans, received the Holy Spirit at the very inception of faith. Everything happened so fast and powerfully that there was no opportunity for any ritual action!

The one precondition (as we have earlier noted) for receiving the Holy Spirit is faith: not faith and something else.14 Baptism, for all its importance, cannot function as a precondition or prerequisite for the reception of the Holy Spirit.15

Now we need to add that neither is water baptism to be understood as a channel for the gift of the Holy Spirit. In none of the narratives in Acts is there representation of the Holy Spirit as being given through water baptism. Though there may be a close approximation of water baptism to the gift of the Spirit, there is no suggestion that such baptism is the medium or channel. Even less is there any picture of water baptism as conferring the gift of the Spirit, there is no suggestion that such baptism is the medium or channel. Even less is there any picture of water baptism as conferring the gift of the Spirit. The Holy Spirit comes from the exalted Lord who Himself confers the gift, and surely does not relegate such to a rite conducted by man.

Indeed, we should add, there is obviously no essential connection between water baptism and the gift of the Holy Spirit. It might be supposed that, though water baptism is not a precondition for the gift of the Holy Spirit, whenever such baptism occurs it is the outward form for the occurrence of the inward spiritual reality. From this perspective it is not so much that water baptism conveys or confers the gift of the Spirit as that the two are related as the outward to the inward; accordingly, water baptism and the gift of the Spirit, or Spirit baptism, make one united whole. According to this view, wherever there is water baptism there is also Spirit baptism: the visible action and the spiritual grace are essentially one.16 However, to answer, we must emphasize strongly: there is no essential connection between water baptism and Spirit baptism,17 no relation of one to the other as outward to inward. The reason: they are dealing with two closely related but nonetheless different spiritual realities. Water baptism is for another purpose than the reception of the Holy Spirit, and unless such is clearly seen there will be continuing confusion. We now turn to this matter.

Fourth, water baptism is connected with the forgiveness of sins. Here we arrive at the important point that water baptism is related primarily to the forgiveness of sins. To use the language of Peter at Pentecost: it is "for" the forgiveness of sins. "Repent and be baptized …in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins." The climactic spiritual reality Peter attests to is the gift of the Spirit, but there is also the reality of forgiveness of sins which is first mentioned, and it is with the spiritual reality that water baptism is directly connected.

What then is the connection? We turn again to the statement of Peter in Acts 2:38 that baptism in Jesus' name is "for the forgiveness of your sins." The word eis, "for," could suggest "for the purpose of," "in order to obtain," thus requirement for forgiveness to be received. However, eis may also be translated "concerning," "with respect to," "with reference to," "with regard to,"18 and thus designates baptism as having to do with forgiveness but not necessarily for the purpose of obtaining it. Either translation is possible, although the latter would seem more likely in that there is no suggestion elsewhere in Acts that water baptism of itself obtains forgiveness. The point then of Acts 2:38 is not to specify water baptism as a requirement for forgiveness of sins; for forgiveness of sins comes by faith not by baptism, but when baptism does occur it is specifically related to that forgiveness.

What then is the nature of the relationship? The answer would seem to be, first, that while water baptism does not of itself obtain forgiveness—hence, is not required for that purpose—it does serve as a means. Forgiveness comes from faith in the exalted Lord; thus it is He who grants forgiveness; it can be obtained no other way. Nonetheless, the channel or means for this forgiveness to be received is water baptism. This doubtless was the case for the 3000 who responded affirmatively to Peter's message: "Repent, and be baptized, every one of you for the forgiveness of your sins." Being baptized, each one of them, was a visible, tangible expression of faith and repentance, an outward cleansing, through which forgiveness was mediated. Thus water baptism was the means of receiving the grace of forgiveness and new life.

It would be a mistake, however, to view this as baptismal regeneration in the sense that the water itself, or the act of baptism, brings about forgiveness and new birth. On a later occasion Peter says: "God exalted him at his right hand as Leader and Savior, to give repentance to Israel and forgiveness of sins" (Acts 5:31). Here though Peter again (as in Acts 2:38) refers to repentance and forgiveness, there is no mention of water baptism but only of the exalted Lord who gives both repentance and forgiveness, and therefore new birth. Hence, when—as in Acts 2:38—water baptism is specified, it is obvious that such a rite does not, and cannot, bring about forgiveness and regeneration. But—and this is important—whenever water baptism is administered in the context of genuine faith and repentance, that baptism does serve as the medium for forgiveness to be received.

A second answer to the matter of the relationship of water baptism brings about, and signifies becoming a new creation. It is a public demonstration of the totality of the divine forgiveness19 and the complete cleansing and renewal that Christ accomplishes. Such baptism, since it is in Christ's name, testifies that in and with Him there is death and burial of the self and resurrection into newness of life.20 Forgiveness is the remission of sins—and remission is nothing less than a release from all that is past and the beginning of the wholly new. Water baptism thus is peculiarly the sign of the forgiveness of sins.

On the other hand, water baptism functions as a seal of faith and forgiveness. It is a tangible impression and certification of the reality of the remission of sins. In the waters of baptism there is "brought home" to a person the wonder of God's total cleansing: the spiritual reality of complete forgiveness being mediated and confirmed in the totality of the baptismal experience. In the combination of the divine gift and the corporal action there is a sealing of the two: what is received in faith is confirmed in the waters of baptism. One who is so baptized in faith is a marked person—cleansed, forgiven, made new in Jesus Christ.21

Now we return to our original point, namely, that water baptism is directly connected with the forgiveness of sins. The specific nature of that relationship (which we have just been discussing) is less important for our concerns than the fact of the connection. The reason for emphasizing this point is that frequently this connection is not seen and water baptism is mistakenly viewed as having directly to do with the gift of the Holy Spirit. It is quite important to keep this matter clear, or there will be continuing confusion in this vital area.

Before leaving the discussion of water baptism it is important to add that though such baptism is not directly connected with the gift of the Holy Spirit this does not mean that there is no relationship. On the contrary, where there is faith and forgiveness mediated through water baptism, the Holy Spirit is indubitably at work. It is the Holy Spirit who empowers the word of witness, convicts of sin, thus bringing about repentance. Here then by the Holy Spirit is the origin of faith that leads to the forgiveness of sins and baptism in the name of Christ. All of this is apparent, for example, in Acts 2:22-38 where the out-poured Spirit is the agent in each of these matters. Thus the Holy Spirit is very much involved in the whole process of salvation. Since this process may include water baptism, it is the Holy Spirit who gives spiritual significance to the act of baptism (otherwise it is nothing but an empty rite). It is clear then that water baptism is closely connected with the activity of the Holy Spirit.

However—and here is the critical matter—this just-described activity of the Holy Spirit is by no means the gift of the Holy Spirit. The gift ordinarily follows upon forgiveness and baptism, even as a promise attached thereto: "Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. For the promise is to you and to your children and to all that are far off, every one whom the Lord our God calls to him" (Acts 2:38-39). The gift does not have to do with forgiveness, but with what is promised to those who repent and are baptized for forgiveness.22 It is a promise to all whom God calls to Himself—such calling implemented through the working of the Holy Spirit—that they will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Another matter to discuss briefly concerns the formula for water baptism as set forth in Matthew 28:19 being different from that set forth in the book of Acts. We earlier have observed that water baptism is invariably depicted in Acts as being in the name of Jesus only, but we did not actually deal with the fact that in Matthew the formula is a triune one:23 "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit."

Though there is no simple solution to the difference in formula, a few comments relevant to our concerns may be made: first, the longer Matthean statement suggests that water baptism is entrance into24 a new relationship to God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Second, the shorter Lukan formula (in Acts) specifies that at the heart of this relationship is the forgiveness of sins which comes in the name of Jesus Christ (the Son). Third, since in Jesus is "the fullness of the Godhead,"25 baptism in His name only (as in Acts) is actually in relation to the fullness of the divine reality: it is also, by implication, in the name of the Father and Holy Spirit. Thus there is no essential difference between the Matthean and Lukan formulas: the former highlights the fullness of the relationship into which one enters at baptism, the latter specifies the purpose of that baptism.

It might also be suggested that the words about baptism in Matthew which include reference to the Holy Spirit—"in the name …of the Holy Spirit"—emphasize that Christian initiation is also entrance into the sphere of the Holy Spirit's reality and activity. At the heart of such initiation is the forgiveness of sins (to which baptism in the name of Jesus, or the Son, points), but at the same time it is the beginning of a new relationship to the Holy Spirit (to which baptism in the name of Jesus, or the Son, points), but at the same time it is the beginning of a new relationship to the Holy Spirit (to which baptism in the name of the Holy Spirit points).26 By this is meant not only that the Holy Spirit is active in bringing about forgiveness—as we have noted—but that henceforward life is to be lived in the sphere of the Spirit.27 Though this is not identical with the gift of the Holy Spirit, it may be preparation for it, and even a kind of invocation for that gift to be received.

We turn now to a consideration of the relationship between the laying on of hands and the gift of the Holy Spirit. In coming to this matter we will again be reflecting primarily upon the five basic passages in Acts. What part does the laying on of hands play in the reception of the Holy Spirit?28

It is apparent, first of all, that the Holy Spirit may be given without the laying on of hands. Again reviewing the Acts narrative, we observe that in two of five cases, namely, in regard to the gift of the Spirit at Jerusalem and at the centurion household in Caesarea, there is no laying on of hands.

Concerning the Jerusalem narrative two observations may be made: first, it is obvious that there could have been no laying on hands on the 120; as the first disciples they must receive the Holy Spirit before ministering to anyone else. Second, it seems likely that though the 3000 later that day are baptized, they do not receive the laying on of hands. It will be recalled that Peter said: "Repent and be baptized …and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit" (Acts 2:38); but there is no mention of imposition of hands for this gift to be received. Indeed, it is quite probable that Peter, having just experienced the bestowal of the Spirit as a sovereign, unmediated action by the exalted Lord, expected all to receive the gift the same way the 120 had. However, whatever his expectation, it would seem that the 3000 also received without the laying on of hands.

In the Caesarean situation it all happened so fast—"While Peter was still saying this [i.e., still preaching his message], the Holy Spirit fell on all who heard the word" (Acts 10:44)—that there was no time for hands if anybody had been so minded! Incidentally, Peter this time might have expected to lay on hands because of the intervening incident when he and John had laid hands on the Samaritans for the reception of the Holy Spirit (Acts 8:14-17). However, as in Jerusalem, God sovereignly moves and pours out His Holy Spirit upon all who hear.

What we have been describing is by no means an uncommon occurrence in the contemporary spiritual renewal. The Holy Spirit is frequently received with no human mediation of any kind. This may happen at the end of a period of time as at Jerusalem or with the suddenness of a Caesarea, but in neither case has there been the imposition of hands. This extraordinary, unmediated event is for many a source of continuing amazement and wonder.29

It is apparent then—from the biblical record and contemporary experience—that the laying on of hands is not essential for the Holy Spirit to be received. Moreover, there is no suggestion in Acts that, following such a reception, hands are later placed as a kind of confirmation of what has already happened. Any idea of hands as being necessary or confirmatory is ruled out by the evidence.

Perhaps these things are most important to emphasize in relation to churchly traditions that variously seek to canalize the gift of the Holy Spirit. There are those who hold that the Holy Spirit may only be received through the laying on of hands;30 thus without personal ministry the Holy Spirit may not be given. Over against such a binding of the Holy Spirit to an outward action we need to stress the sovereignty of the Holy Spirit to move as He wills.

Second, the Holy Spirit may be given with the laying on of hands. Returning to the Acts record, we observe that in three of the five accounts of the Holy Spirit being received, this occurred in connection with the laying on of hands. Peter and John, ministering to the Samaritans, "laid their hands on them and they received the Holy Spirit"31 (Acts 8:17). At Damascus, Ananias, ministering to Saul, " …laying his hands on him he said, 'Brother Saul, the Lord Jesus who appeared to you on the road by which you came, has sent me that you may regain your sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit'" (9:17). And Paul, ministering to the Ephesians, when he "had laid his hands upon them, the Holy Spirit came on them" (19:6). There is obviously a close connection between the laying on of hands and the gift of the Holy Spirit.

It is apparent once again that water baptism is not placed in an immediate conjunction with the gift of the Holy Spirit. Water baptism, as earlier mentioned, is related to forgiveness of sins, whereas laying on of hands is connected with the gift of the Holy Spirit. The symbolism is unmistakable: water baptism vividly portrays the cleansing of sin in forgiveness, the laying on of hands the external bestowal of the Spirit. Each of the outward acts is congruent with the spiritual reality to be received.

Looking more closely in the Acts narrative at this conjunction of the Holy Spirit and the imposition of hands, we observe that the Holy Spirit may be given through the laying on of hands. Thus it is not only a temporal conjunction, so that the gift of the Holy Spirit coincides with, or follows immediately upon, the laying on of hands; but also an instrumental conjunction, namely, that the imposition of hands may serve as the channel or means for the gift of the Spirit. Just following the words quoted above about the Samaritans (in Acts 8:17), the text reads: "Now when Simon saw that the Spirit was given through the laying on of the apostles' hands …".32 The word "through" (dia) specifies the instrumentality of hands in the reception of the gift of the Holy Spirit. The laying on of hands is thus the means of grace whereby the Holy Spirit may be received.

The laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Spirit has continued variously in the history of the Church. The practice belongs particularly to the Western tradition of Christianity, but with diverse understanding of what is conveyed in the gift. Sometimes it is assumed that through the laying on of hands there is the completing or perfecting of what was given earlier in water baptism; or, again, it is held that water baptism needs no completion or perfection, so that what happens through the imposition of hands is rather a confirming or strengthening of the person for the Christian walk. However, there is seldom in the traditional church any expectation that through the laying on of hands an extraordinary spiritual event will take place, namely, the gift of the Spirit as the veritable outpouring of God's presence and power.

Here, again, is where the contemporary spiritual renewal is recapturing the biblical witness. Through the laying on of hands, people are receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit, not in the sense of completion or perfection of confirmation (though it may include elements of both), but in the sense of a divine visitation so overwhelming as to release extraordinary praise and channels of powerful ministry. There is the exciting expectation that when hands are laid on a person, the Holy Spirit Himself will be given.33

Here two points need emphasis: first, as we have already observed, there is no necessity for hands to be laid on persons for them to receive the Holy Spirit. The exalted Lord may dispense with all ordinary means and sovereignly pour forth the Holy Spirit. Second, though the Holy Spirit may also be given through the laying on of hands, it would be a mistake to assume that this happens invariably, i.e. by virtue of the objective action.34 We have earlier commented that faith—believing—is the essential element in the reception of the Holy Spirit; thus in all the biblical incidents of the laying on of hands it is upon believers that hands are laid. For only those who believe in Jesus Christ may receive from Him the blessed gift of the Holy Spirit.

What then is the importance of the laying on of hands? If, on the one side, there is no necessity, and if, on the other, there is no guarantee, why not dispense with such? The answer would seem clear: the laying on of hands is a divinely instituted means of enabling persons to receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. Hands signify contact, community, sharing—a human channel for the divine gift; the laying on of hands represents, as seen earlier, the coming of the Holy Spirit upon someone.35 Thus, though a person may receive the gift of the Holy Spirit without human mediation, the imposition of hands may greatly facilitate this reception.

Third, the laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Spirit is not limited to the apostles. As we have noted, the apostles Peter and John do minister the Spirit to the Samaritans and the Apostle Paul does the same for the Ephesians. However, it is a Christian brother, Ananias, with no claim to apostolic authority,36 who is the minister of the Holy Spirit to Saul of Tarsus. Thus, it would be a mistake to interpret the words of Acts 8:18—"The Spirit was given through the laying on of the apostles' [Peter and John's] hands"—as the only way it could happen. Since Ananias, a lay brother, could minister the Holy Spirit to Saul, there is no inherent reason that Philip, the deacon-evangelist, could not have done the same for the Samaritans.37

A few words might be added about the ministry of Ananias to Saul. Though little is said about him, a few things stand out: first, he was a man of faith and prayer, the Lord speaking to him in a vision: "The Lord said to him in a vision, 'Ananias.' And he said, 'Here I am, Lord'" (9:10). Second, he was a man of obedience, for though, because of Saul's evil reputation, he first hesitated at the command of Christ—"Rise and go" (9:11)—he nonetheless went. Third, Ananias, as later described by Paul, was "a devout man according to the law, well spoken of by all" (22:12), hence a man of strong character and perhaps peculiarly prepared through his devotion to the law to minister to Saul the Pharisee. Thus, it may be suggested, a combination of factors made Ananias an effective minister of the Holy Spirit, and particularly suited to exercise the role of ministering to Saul's need.

It would seem apparent that the basic qualification for the laying on of hands is not apostolic office but other more important matters. And so it continues into our own day and generation. Countless numbers of people are receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit through the ministry of lay people. To be sure, many "official" clergy are likewise ministering the Holy Spirit with great effectiveness.38 However, what really counts is not office (not even "apostolic succession") but attributes such as faithfulness, prayer, readiness, obedience, devoutness and boldness. The ministering of the Spirit, including the laying on of hands, is happening through such Christian people everywhere. Indeed, this ministry belongs to the whole people of God.

ENDNOTES

1. This will be noted hereafter especially in connection with Acts 19.

2. Three prepositions are used: epi (Acts 2:38); eis (8:16 and 19:5), and en (10:48). They could be translated "upon," "into," and "in." For all three, "in the name" is the usual English translation. This seems proper, since the Greek words do not, I believe, intend a difference.

3. The formula in Acts therefore is obviously divergent from the triune emphasis of Matthew 28:19. We shall return to this later.

4. As we use the term "water baptism" from now on, we shall ordinarily be referring to baptism in the name of Christ.

5. These verses, depicting a community of people devoted to the apostles' teaching, fellowship, prayer, community, sharing and climactically "praising God and having favor with all the people," strongly suggest a participation in the gift of the Holy Spirit. (See Chapter 2, supra, especially on the note of praise.)

6. Another reason sometimes given for the Samaritans not receiving the Holy Spirit until after their water baptism is that the gift of the Spirit requires apostolic ministry; Philip as an evangelist could not minister the Holy Spirit, so the apostles Peter and John must come down to fulfill that function. This line of reasoning, however, seems invalid both from the perspective of the immediate context which does not intimate that Peter and John come vested with some special sacerdotal authority, and also in light of what happens later in Acts 9 when Ananias, who is a layman, ministers the Holy Spirit to Saul of Tarsus. (See below, under "laying on of hands," for more details.)

7. F.D. Bruner, in his A Theology of the Holy Spirit, has the peculiar statement: "The Spirit is temporarily suspended from baptism here 'only' and precisely to teach the Church at its most prejudiced juncture, and in its strategic initial missionary move beyond Jerusalem, that suspension cannot occur (italics: Bruner), p. 178. I should think that the passage teaches exactly the opposite: that suspension may occur. Bruner's interpretation is actually not based on the text but on a prior view (shown many times in his book) of the inseparability of water baptism and the gift of the Spirit.

8. There is some variation here. Those in the more Protestant tradition of the movement do not hesitate to recognize a gift of the Holy Spirit after water baptism; they see it in the biblical record, and they claim to have experienced it. Those in the Catholic tradition (Roman and Anglo-) of the movement sometimes express the view that the Spirit is given in baptism or confirmation, and that the "Pentecostal experience" rather than being a reception of the Spirit is a "realization" or "actualization of that gift." See, e.g., Catholic Pentecostals which speaks of "an individual's or community's baptismal initiation," being "existentially renewed and actualized" (p. 147), and Leon Joseph Cardinal Suenens' A New Pentecost? listing of various expressions: "a release of the Spirit, a manifestation of baptism, a coming to life of the gift of the Spirit received at confirmation" (p. 81).

9. Reference might also be made to the account in Acts 8:28-39 of Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch. The eunuch comes to faith, is baptized by Philip, and "When they came up out of the water, the Spirit of the Lord caught up Philip" (8:39). According to some early manuscripts the text reads: "And when they came up out of the water, the Holy Spirit fell upon the eunuch and an angel of the Lord caught up Philip." The point of this reading is undoubtedly to emphasize that, as with the Samaritans, the eunuch's baptism was followed by the gift of the Holy Spirit. (See F.F. Bruce's statement to this effect in his commentary, The Acts of the Apostles [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1951], p. 195.) Thus, in addition to the accounts in Acts that specify the gift of the Spirit to follow water baptism, such may be implied in Acts 8:39.

10. Donald L. Gelpi. S.J. in his Pentecostalism: A Theological Viewpoint (New York: Paulist Press, 1971) suggests the case of a "Robert Z" who "a week before his sacramental baptism, while attending a prayer meeting …receives Spirit-baptism and immediately begins praying in tongues," p. 178. Probably Father Gelpi had witnessed this, since he refers to such as "concretely possible." However, the problem for Catholic theology is simply this: how does one relate such an experience to the traditional view that the Holy Spirit is received in baptism or confirmation? (In this case it does not help to speak of Spirit-baptism as the actualization of the gift of the Spirit received in the sacraments when there has been no sacramental participation!)

11. According to Matthew 28:19.

12. There are instances in the contemporary spiritual renewal of persons who received baptism as infants being baptized as adults. In some instances such adult baptism is sought because of a growing conviction of the invalidity of infant baptism; in other cases, adult baptism is viewed as not denying the validity of infant baptism, but as its fulfillment through personal, believing participation. Generally speaking, however, people in the renewal who have had prior baptism do not follow this pattern. I am referring, therefore, in the text above to those who have had no prior experience of baptism now becoming participants.

13. Possibly all—but the Scriptures give no certain information.

14. Not even the laying on of hands (to which we shall come shortly).

15. Faith alone prepares the way. So Schweizer writes (in specific response to the Caesarean account as interpreted by Peter in Acts 15:8): "Faith, not baptism, purifies for the reception of the Spirit" (article on πνευηα [pneuma] in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Vol. VI, p. 414).

16. In the words of F.D. Bruner: "Baptism and the reception of the Spirit are so synonymous as to be identical. Christian baptism is spiritual baptism" (op. cit., p. 190). This view, fortunately, is not held by James Dunn who says, "Spirit-baptism and water baptism remain antithetical" (op. cit., p. 227).

17. E. Schweizer in his analysis of the Spirit in Acts writes that "the Spirit is not tied to baptism. Once He comes on men before baptism (10:44), once without it (2:1-4), once on a disciple who knew only John's baptism (18:25)" (op. cit., p. 414).

18. For example, note the earlier use of eis in the same chapter, verse 25, where Peter prefaces a quotation from a Davidic psalm thus: "For David says concerning him [the Christ]." The word translated "concerning" (RSV and KJV) is eis. eis here clearly means "regarding," "in reference to," etc. For other similar use of eis cf. Romans 4:20 (eis translated as "concerning" in KJV).

19. Water baptism as immersion—the whole body covered—best symbolized this. However, the pouring of water over the person may likewise represent this totality. Sprinkling (in accordance with Ezekiel 36:25, "I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and you shall be clean from all your uncleannesses") is a third possibility.

20. E.g., see Romans 6:4—"We were buried …with him by baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead …we too might walk in newness of life" (cf. Colossians 2:12 and Galatians 3:27). Water baptism by immersion most vividly demonstrates burial and resurrection.

21. This matter of baptism as sign and seal relates to what Paul says, in Romans 4:11, concerning how Abraham "received circumcision as a sign or seal (semeion elaben peritomes sphragida of the righteousness which he had by faith while he was still uncircumcised." Water baptism is clearly the New Testament parallel, and thus no more than circumcision brings about righteousness or forgiveness, but is a sign and seal of it.

22. As earlier noted, water baptism is not so integral a part of forgiveness that it may not occur later. Particularly recall the account of the Caesareans in Acts 10:43-48. However, ordinarily the sequence is that of Acts 2:38-39.

23. Mention was made of this formula in footnote 3 above, but there was no elaboration of its significance.

24. The Greek word "in" ("baptizing them in …") is eis which though it may simply mean "in" (see footnote 2) may also be translated "into." As we have earlier noted, eis may also signify "with reference to," hence "in relation to."

25. For in him the whole fullness of deity [to pleroma tes theoetos—"the fullness of the Godhead" KJV] dwells bodily" (Colossians 2:9).

26. The same thing is true about the Father—a new relationship to him: by adoption one becomes a son of God and is able to address God as "Father" (cf. Romans 8:15; Galatians 4:5-6).

27. In my book, The Pentecostal Reality (Plainfield, NJ: Logos, 1972), chapter 6, "The Holy Trinity," I wrote: "The purpose of that part of the Great Commission, 'Go therefore …baptizing' is not to make learners out of people in regard to God, but to introduce them into life lived in the reality of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit" (p. 102). On the matter of the Holy Spirit, later words are: "This means life claimed by God through Jesus Christ in a total kind of way, the Spirit of the living God probing the depths of the conscious and the unconscious, releasing …new powers to praise God, to witness compellingly in His name, to do mighty works that only He can do. Do we know this?" (p. 107).

28. There are other instances in Acts of the imposition of hands which are not directly concerned with the gift of the Holy Spirit: Acts 6:6—the dedication of seven "deacons"; 13:3—the commissioning of Barnabas and Saul; and 28:8—the healing of Publius' father. While such instances of the laying on of hands are not for the gift of the Spirit, they obviously represent Spirit-inspired activities.

29. The earliest testimonies in Catholic Pentecostals, "Bearing Witness," pp. 24-37, of students who were baptized in the Holy Spirit at the "Duquesne weekend" especially depict an unmediated happening. One participant testifies: "There were three other students with me when all of a sudden I became filled with the Holy Spirit and realized that 'God is real' … . The professors then laid hands on some of the students, but most of us received the 'baptism in the Spirit' while kneeling before the blessed sacrament in prayer" (pp. 34-35). The Acts of the Holy Spirit [among Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists, etc.] contains a large number of testimonies of the Holy Spirit being given without the laying on of hands.

30. Or, as we have noted, through water baptism. Sometimes the view is entertained that there may be two gifts of the Holy Spirit: one at water baptism and the other with the imposition of hands.

31. Literally, they "were laying [epetithesan—imperfect tense] their hands on them and they were receiving [elambanon—also imperfect] the Holy Spirit." The Greek tense suggests an action over a period of time, and possibly that the Samaritans one by one were receiving the Holy Spirit.

32. The text continues with the recitation of Simon the magician's vain and sordid attempt to buy the power to confer the gift of the Spirit through his own hands. However, despite his perfidy, there is no question in the text that Simon correctly perceived it to be through the laying on of Peter and John's hands that the Holy Spirit was given.

33. See, for example, the second set of testimonies in Catholic Pentecostals, "Bearing Witness," pp. 58-106, having to do with Notre Dame. Most cases of baptism in the Spirit occurred through the laying on of hands. (It might be suggested that Duquesne was more like the first unmediated biblical outpourings on Jews and Gentiles at Jerusalem and Caesarea, Notre Dame more like secondary outpourings upon Samaria and Ephesus.) Incidentally, I think Father Gelpi is on the right track in not seeking to relate Spirit-baptism to either water baptism or confirmation (as some Catholic theologians do): "Spirit baptism is not a sacrament but is a prayer for "full docility to the Spirit of Christ" (p. 183).

34. E.g., the traditional Roman Catholic view of sacraments (baptism, confirmation) as being efficacious "ex opere operato"—"by the work performed." Father Kilian McDonnell, while holding that "the fullness of the Spirit is given during the celebration of initiation," speaks of "the scholastic doctrine of ex opere operantis [wherein] we receive in the measure of our openness." Thus, though there is an objective—in that sense invariable—gift of the Spirit in "the celebration of initiation," there is no receiving without subjective appropriation. (This quotation may be found in an article entitled, "The Distinguishing Characteristics of the Charismatic-Pentecostal Spirituality" in the magazine One in Christ, 1974, Vol. X, No. 2, pp. 117-18.) Despite my appreciation of Father McDonnell's attempt to relate the reception of the Spirit to sacramental rites, I think it is too limited a view. For while ex opere operantis is surely an important concept in the matter of sacramental appropriation, it is inadequate in objectively by sacramental action (whether of baptism or confirmation) ex opere operato, there may be nothing to receive ex opere operantis.

35. Father Edward O'Connor in his book, The Pentecostal Movement in the Catholic Church (Notre Dame: Ave Maria Press, 1971) writes: "The gesture [of laying on of hands] does symbolize graphically the fact that God's grace is often mediated to a person through others, and especially through the community. God seems to bless the faith from which this prayerfully gesture proceeds; again and again people find that they have been helped in a powerful and manifest way by it …the baptism in the Spirit is usually received thus" (p. 117).

36. Ananias is simply described in Acts 9 as "a disciple at Damascus" (v. 10).

37. It is interesting that when Philip later proclaims the gospel to the Ethiopian eunuch, and baptizes him (Acts 8:38), the next words according to the Western text (as we earlier noted) are: "And when they came up out of the water, the Spirit of the Lord fell upon the eunuch." Though this is likely a later textual addition, it does reflect some early church understanding that Philip was by no means dependent on apostolic help for the Holy Spirit to be given.

38. In my book, The Era of the Spirit, I sought to summarize the laying on of hands thus: "Wherever this laying on of hands occurs it is not, as such, a sacramental action. It is, rather, the simple ministry by one or more persons who themselves are channels of the Holy Spirit to others not yet so blessed. The 'ministers' may be clergy or laity; it makes no difference. …Obviously God is doing a mighty work today bound neither by office nor by rank" (p. 64).

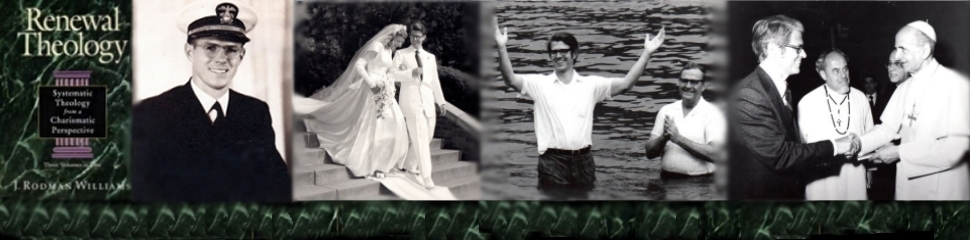

Rodman Williams, Ph.D., was a Professor of Renewal Theology Emeritus at Regent University School of Divinity. Author of numerous books, he is perhaps best known for his three volume Renewal Theology (Zondervan, 1996).

Unless otherwise indicated, all scriptural quotations are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible.

The Gift of the Holy Spirit Today by J. Rodman Williams, was published in 1980 by Logos International.

Content Copyright ©1996 by J. Rodman Williams, Ph.D.

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Top