Renewal Theology

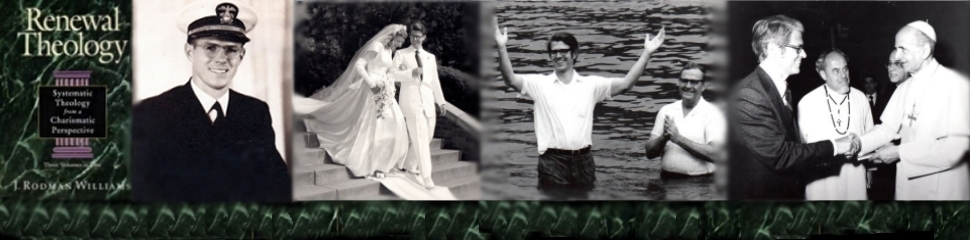

featuring the works of theologian J. Rodman Williams

Renewal Theology

- Home

- About Renewal Theology

- Renewal Theology Reviews

- Renewal Theology Excerpt and Online Bookstores

- Audio Teachings

Media

Published Online Books

A Theological Pilgrimage

- Preface and Personal Testimony

- 1. Renewal in the Spirit

- 2. A New Era in History

- 3.The Upsurge of Pentecostalism

- 4. The Person & Work of the Spirit

- 5. Baptism in the Holy Spirit

- 6. The Missing Dimension

- 7. The Charismatic Movement & Reformed Theology

- 8. God's Mighty Acts

- 9. Why Speak in Tongues?

- 10. The Holy Spirit & Eschatology

- 11. A Pentecostal Theology

- 12.The Greater Gifts

- 13. Biblical Truth & Experience

- 14. Theological Perspectives of the Pentecostal/Charismatic Movement

- 15. The Gifts of the Holy Spirit and Their Application to the Contemporary Church

- 16. The Engagement of the Holy Spirit

- Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Conclusion

The Gift of the Holy Spirit Today

Ten Teachings

- 1. God

- 2. Creation

- 3. Sin

- 4. Jesus Christ

- 5. Salvation

- 6.The Holy Spirit

- 7. Sanctification

- 8. The Church

- 9. The Kingdom

- 10. Life Everlasting

The Pentecostal Reality

- Preface

- 1. The Pentecostal Reality

- 2. The Event of the Spirit

- 3. Pentecostal Spirituality

- 4. The Holy Spirit & Evangelism

- 5. The Holy Trinity

Published Online Writings

Prophecy by the Book

- 1. Introduction: The Return of Christ

- 2. Procedure in Studying Prophecy

- 3.The New Testament Understanding of Old Testament Prophecy

- 4. Israel in Prophecy

- 5. The Fulfillment of Prophecy

- 6. Tribulation

- 7. The Battle of Armageddon

- 8. The Contemporary Scene

Scripture: God's Written Word

- 1. Background

- 2. Evidence of Scripture as God's Written Word

- 3. The Purpose of Scripture

- 4. The Mode of Writing

- 5. The Inspiration of Scripture

- 6. The Character of the Inspired Text

- 7. Understanding Scripture

The Holy Spirit in the Early Church

Other Writings

The Pentecostal Reality

Chapter 1 - The Pentecostal Reality

In the "worldwide Pentecost" now occurring I should like to set forth some of my reflections under the heading of "The Pentecostal Reality." I do this with more than a little excitement because of my conviction that this is a movement of the Holy Spirit which has great significance for the whole of Christendom. For the sake of clarity and conciseness I shall summarize my thoughts in five basic statements.

1. The most important happening in the church today is the rediscovery of the Pentecostal reality.

There is much transpiring in the life and activity of the church that can lay claim to being of critical importance. One has only to recall the variety of things happening in such areas as confessional restatement, liturgical reform, improvement in evangelistic methods, search for new forms of ministry, concern for more relevant social involvement, and multiple ecumenical activity. The church today is obviously in much ferment and seeking almost desperately to discover some secret, some strategy whereby it can find its way in a very difficult time. In the midst of all of this a strange thing—exciting to many, baffling to others—is also occurring which seemingly has little relation to these various things, namely, the rediscovery of the Pentecostal reality.

This rediscovery is of such foundational importance that the whole church needs seriously and openly to consider it. By no means is there any intention of discounting the significance of the church's varied efforts in faith and life—for God is surely at work in many ways. But beyond these something is happening in the lives of many people of so vital a nature as to make possible new impulses of power for the complete round of Christian activity. Nothing therefore in the life of the church today calls for more urgent consideration than this contemporary rediscovery of the Pentecostal reality.

2. By "the Pentecostal reality" is meant the coming of God's Holy Spirit in power to the believing individual and community.

Among countless numbers of people today in many churches an event or experience is happening which makes vivid the narrative of Acts 1 and 2 as contemporary event. What they may have considered before as more or less interesting history of the first days of the church—and some of it rather strange (especially Acts 2:1-4)—has suddenly become personally real. For they too have experienced a coming of the Holy Spirit wherein God's presence and power has pervaded their lives. It may not have been quite like "wind" and "fire," but they do confess, in joy and humility, that they know what it means to be "filled with the Holy Spirit." There has been a breakthrough of God's Spirit into their total existence—body, soul, and spirit—reaching into the conscious and subconscious depths, and setting loose powers hitherto unknown. Through the operation of the Holy Spirit many have found themselves (like those on the Day of Pentecost) speaking in "other tongues" and declaring the mighty works of God in ways transcending all human ability. Power is there—and this includes a heightened capacity to witness to others about the grace of God in Jesus Christ. By the Holy Spirit there is fresh courage and boldness, and however faulty the human words, they carry conviction because they come freighted with the power of the Holy Spirit. The minds and hearts of those who hear are intensely probed by the Spirit, and many find new life and salvation. But this is not the whole story, because the powers set loose are not only those energizing witness (whereby God is extraordinarily praised and men are deeply moved), but also those whereby "wonders and signs" are now performed (cf. Acts 2:43). Multiple acts of healing and deliverance, previously unimagined, now become a part of ongoing Christian life.

This, as described, is something of "the Pentecostal reality." There is nothing here totally foreign to what Christians have always known and experienced; however, this reality signifies a breaking in of the Holy Spirit with such effect as to point to a further dimension of His operation. Thus there is both familiarity and strangeness to the church at large—as it stands today in the midst of the Pentecostal reality.

A word needs to be added about the background of those for whom the Pentecostal reality has become personal experience. They all came into this through believing in Jesus Christ. Many had been devoted servants of Christ long before it occurred, others only a short time, some found it happening at the moment of their coming to faith. All however had experienced His forgiveness and received His grace. But at whatever time the Pentecostal reality occurred, they knew that it came from Jesus Christ; it was He through whom the Spirit was poured out (cf. Acts 2:33).

3. The "rediscovery" refers to the fact that for the church as a whole this experience of the Pentecostal reality represents the coming to light of a dimension of the Holy Spirit's activity that has long been unrealized or overlooked.

The word "rediscovery" is quite appropriate because what is happening today is an opening up of truth long neglected. For many it is so new, even startling, that it is hard to believe that the Pentecostal reality is a possibility within Christian faith. On the other hand, when the discovery is made, and a person enters into it, he may wonder how it could have been missed for so long! However, if he turns joyfully to his church to testify to what has happened, quite often there is antagonism and opposition—as if the Pentecostal reality were a foreign foe. Thus frequently is repeated, though at a different point, the situation of Martin Luther. His experience of "free grace" was likewise strange to many in the church of his day, and as a result Luther found himself, while praising God for this momentous rediscovery, being ostracized by his own people. Truth, re-opened and re-lived, does not set well with tradition long established.

What, we may ask, happened in the long tradition of the church to the knowledge and experience of the Pentecostal reality? Two things at least should be noted. First, in the Catholic tradition there has been the tendency to "sacramentalize" this reality and experience. Beyond the sacrament of baptism (wherein, according to Catholic teaching, regeneration occurs and Christian life begins) there is the sacrament of confirmation in which there is the laying on of hands for the strengthening of the believer in the service of Christ. The scriptural basis often adduced is that of Acts 8:4-17, which makes a clear differentiation between baptism and the later reception of the Holy Spirit through the laying on of hands. In this confirmation the Holy Spirit is said to be given as He was to the apostles at Pentecost, and the result is that an "indelible character" is printed upon the recipient whereby his strengthening occurs. But—and here a critical question must be raised—what are the evidences that the Pentecostal reality has actually been experienced? Whatever may have been symbolized (or even objectively mediated) by the sacrament, does the confirmand ordinarily exhibit the signs of a genuine Pentecostal occurrence? The answer unfortunately must be no. Thus one can only conclude that the "sacramentalizing" of this reality has had the effect of formalizing it and thereby failing to make actual the inward experience.

Second, in the tradition of many Protestant churches, there is little or no emphasis placed on confirmation; accordingly, it is understood that the Pentecostal reality (insofar as it is considered) is included in baptism and/or regeneration. Variously it is suggested that since baptism is also "in the name of the Holy Spirit," this includes the Pentecostal "outpouring," or—particularly where "believer's baptism" is the pattern—that conversion, rebirth, regeneration, etc., is identical with the Pentecostal experience. The former understanding suffers the same problem, as above mentioned, namely, the lack of personal experience. Even if there is something given in baptism, what about the inward appropriation? The latter interpretation, which identifies conversion with the Pentecostal reality, is quite difficult to maintain. By what stretch of the imagination can one see in the original Pentecostal event of Acts 2:1-4 an experience of conversion or regeneration? Also Acts 8:4-17 has to be disregarded or misinterpreted (here the Catholic tradition, despite its sacramentalism, is closer to Scripture than much Protestantism). Thus the Pentecostal reality eludes both traditional Catholicism and Protestantism through either a sacramentalism which formalizes the experience or an emphasis on baptism/regeneration that overlooks it!

It is scarcely an exaggeration, therefore, to say that this rediscovery of the Pentecostal reality in our day is of vast importance. For it is not some theological or biblical matter of relatively minor significance, but concerns the whole dimension of power which is available for Christian life and witness. To be sure, there is no genuine belief in Jesus Christ that is possible without the Holy Spirit (since it is He who makes faith in Christ effectual), and no consequent discipleship which is without the Holy Spirit's leading and instruction (cf. Acts 1:2). Thus the Holy Spirit is at work in all Christian faith and practice. But this must not be identified with the Pentecostal reality which is none other than the coming of the Holy Spirit to anoint the people of God with power for extraordinary praise, speech that breaks open the hardest of hearts, the performing of signs and wonders, and a boldness of witness and action that can transform the world.

4. The word "happening" suggests that the Pentecostal reality is event, occurrence, action, and takes place in the context of God's free promise and man's open readiness.

The "promise of the Father" (Acts 1:4) which is the "promise of the Holy Spirit" (Acts 2:33) is the assurance that stands behind the Pentecostal event. It is a promise not only to the original disciples but also to those after them who believe: "For the promise is to you and your children and to all that are far off, every one whom the Lord our God calls to him" (Acts 2:39). Thus the Pentecostal reality is no chance occurrence, limited in scope, but is the fulfillment of the unfailing promise of God the heavenly Father. Accordingly, those whom God calls to Him in every generation are without exception assured that the Pentecostal reality is available to them. Those in our day for whom Pentecost has become a living experience have not hesitated to take God at His word and believe in His promise.

Because the promise is free, the Holy Spirit comes as a gift. The Pentecostal reality, therefore, is none other than "the gift of the Holy Spirit" (Acts 2:38; cf. 11: 17). As a gift it cannot be earned but comes as a gracious bestowal from God the Father to His sons through Jesus Christ. Those who receive this blessing can never claim to have gained it by work or merit. One who has experienced the Pentecostal reality, therefore, can only be gladly and humbly thankful for God's gracious action.

The other side of the picture is that of openness and readiness for the promised gift. The promise is assured those who wait upon the Lord (Acts 1:4); it happens to those who devote themselves to prayer (Acts 1: 14); the Spirit is given those who obey the Father (Acts 5:32). Though the gift may not be earned, it may be asked for. Indeed, the very asking (even seeking and knocking) represents the kind of readiness which is the human context for the heavenly gift—so "will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him" (Luke 11: 13).

What many have found to be quite important is the need for total yieldedness to God's possession. When from the human side there is surrender of the complete self (including, perhaps climactically, the tongue!), a willingness to let go everything for the sake of the Gospel—including reputation and security—and an emptiness of self before the Lord, He may then move in to fill the person with His power and presence.

But the sovereign God remains the free disposer of His gift of the Holy Spirit. He has promised it, so we need not doubt its coming; and if we ask, He will surely answer. But there is no guarantee as to exactly when it will take place, nor under precisely what circumstances. It happened suddenly at the Jerusalem Pentecost (Acts 2:2), surprisingly at the Gentile Pentecost (Acts 10:44), and, in our day, the element of suddenness and surprise has by no means ceased! There is simply no point at which—regardless of the number of prayers offered, the quality of yieldedness, or whatever else may be done—we can be sure of the Spirit's coming. God remains the sovereign Lord.

5. The fact that the Pentecostal reality is being rediscovered in "the church today" could bring about a renewal of incalculable proportions.

It is imperative that the church of today be fully acquainted with the nature of the Pentecostal reality and adopt a positive attitude toward its occurrence. Reference has been made to the opposition that often has developed against it. Doubtless, fault lies partly among those of Pentecostal experience who in many cases have misguidedly represented its significance (e.g., as a kind of superior Christianity—or even "the real thing") and thereby brought about disharmony and division. But this is only a small part of the total picture, for often, regardless of the adequacy of the witness, antipathy has been aroused. This is quite understandable in light of the fact that the tradition of the church (as noted) and, even more, the long-inherited structure of Christian faith and practice has had no adequate place for the Pentecostal experience. The Pentecostal reality thus appears as a threat; and for the sake of protecting what is already established, strong efforts are often made to repel an apparently foreign body. But now it is fervently to be hoped that, with more adequate understanding of what the Pentecostal reality means, and its signal importance for the full life of the church, a new, positive, and expectant attitude can develop.

Even more, however, than just developing a positive attitude, the church at large needs to open itself to the Pentecostal reality. There is a growing recognition among many people in the church today—clergymen and laity alike—that at the heart of much of our life and activity a deep spiritual crisis exists. Despite multiple attempts by the church at reassessment and relevance, there remains the haunting sense of something lacking or unfulfilled and a feeling of spiritual impotence. How tragic indeed when the church was intended to be a dynamic fellowship of the Spirit through whom the world is transformed! Thus, nothing is so urgent for the church throughout the world as to heed the word of the Lord: "Stay...until you are clothed with power from on high" (Luke 24:49). Who can begin to imagine the full scope of what might happen if the church took that command seriously?

| Preface | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Top |

Content Copyright ©1997 by J. Rodman Williams, Ph.D.